Review Article - Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses ( 2022) Volume 0, Issue 0

The Use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Anxiety and Depression

Motahhareh Isarizadeh1, Tahereh Sadeghiyeh2, Seyedeh Sara Naghib Hosseini3, Saeid Motevalli4 and Mohammad Saleh Shokouhi Qare Saadlou4*2Department of Psychiatric, Shahid Sadoughi University, Yazd, Iran

3Department of Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Bandar Abbas, Iran

4Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences abd Liberal Arts, UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Mohammad Saleh Shokouhi Qare Saadlou, Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences abd Liberal Arts, UCSI University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Email: jouyanr@gmail.com

Received: 15-Dec-2021, Manuscript No. CSRP-21-50606; Editor assigned: 17-Dec-2021, Pre QC No. CSRP-21-50606(PQ); Reviewed: 31-Dec-2021, QC No. CSRP-21-50606; Revised: 05-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. CSRP-21-50606(R); Published: 12-Jan-2022, DOI: 10.3371/CSRP.IMTS.011222

Abstract

Anxiety and depression are among the most common psychological disorders. However, despite extensive research on effective therapeutic interventions and their promising results, there are still significant shortcomings. In response to these shortcomings, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) emerged as a third wave cognitive therapy to reformulate conceptualization and treatment of anxiety and depression disorders. The purpose of the ACT is to increase engagement in activities that bring meaning, vitality and value to the lives of individuals who experience persistent anxiety, depression, pain and discomfort. The ACT extends previous forms of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and integrates many CBT-related variables into six main therapeutic processes. ACT is a process-based therapy that enhances openness, awareness, and engagement through a wide range of methods, including exposure-based methods, metaphors, and value clarification, and reduces anxiety and stress. This review examines the main features, description, basics, and empirical evidence of ACT as a treatment for anxiety and depression disorders.

Keywords

Anxiety disorders • Depression • Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Introduction

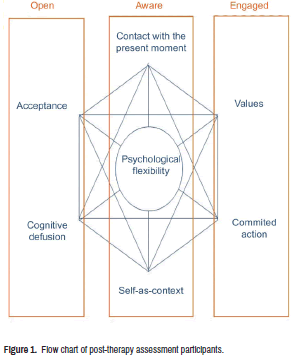

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is a relatively new form of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) that focuses on accepting personal events rather than trying to alter their forms. Through focusing on patients' goals and values, ACT tries to guide the process of behavior change and increase psychological flexibility [1,2]. Therefore, the main goal of ACT therapy is to reduce the rigidity of cognitive integration and empirical avoidance to increase the psychological flexibility of patients about their thoughts, feelings, and behavior through six therapeutic processes including acceptance, cognitive diffusion, self as context, mindfulness, values and committed action [3-5]. Psychological flexibility refers to the capacity of accepting one's own complex personal feelings and thoughts while simultaneously trying to live a meaningful life following personal values [4].

Over a relatively short time since its development, a large number of studies have shown the efficacy of ACT in treating a variety of mental health problems and problem behaviors, including depression and anxiety [6-8]. In a recent study, Lee et al. stated that patients receiving ACT were more flexible than those receiving conventional therapy or CBT-based training and were more likely to show improved physical and psychosocial outcomes [9]. ACT- based therapy has advantages over other conventional psychotherapies, especially CBT [4]. Many problems go along with aging, such as poor health, dysfunction, incurable diseases, and the loss of family or friends may lead to severe anxiety and depression in individuals which cannot be controlled by the control-based strategies promoted by traditional CBT [3,4,10]. These therapies are, therefore, unable to cause gradual improvement in the cognitions and change the life attitudes of these people. Instead, ACT- based therapy seeks to increase the flexibility of individuals and pave the way for a purposeful, value-based life. Finally, unlike CBT, ACT functions as a metacognitive therapy by targeting the core of vulnerability [11,12].

Simply put, ACT is a modern behavior analysis applied to clinical issues, including anxiety and depression [4,12]. Therefore, this study investigates the background, description, basics, therapeutic techniques, and empirical evidence for the ACT as a treatment for anxiety and depression disorders and depression.

Literature Review

ACT background, description, basics, and therapeutic techniques

Developed by Hayes in the late 1980s, the ACT is regarded as a part of the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies that merges CBT elements with mindfulness and acceptance processes [13,14]. As part of the Contextual Behavioral Science (CBS), the ACT adopts the basic assumptions of functional contextualism, which are generally consistent with common assumptions in behavior analysis [15]. The ACT has coherent philosophical- theoretical foundations. ACT is based on behaviorism but relies on the analysis of cognitive processes. Given the increase in empirical evidence, attempts have been made to classify ACT as a distinct and integrated model of behavioral change from CBS [14]. In the philosophic sense, ACT therapy is based on the pragmatic philosophy of functional contextualize and emphasizes workability as a truth criterion. The theoretical dimension of ACT is the Relational Frame Theory (RFT), which is based on cognition and language theory, and indicates that the underlying mechanisms of symbolic language cause discomfort and psychological damage. In RFT, language is considered the main cause of human suffering. It is unusual for a human being to do something without thinking about it in a way that does not involve verbally-based thoughts. Thoughts can turn to aversive functions when they refer to stimuli or events that are painful or unpleasant [16]. Just as people try to escape or avoid unpleasant stimuli or events, they are likely to try to escape or avoid painful or unpleasant thoughts, feelings, emotions, and other disgusting experiences. For example, a person's anxiety about career indecision may be related to their bitter experiences or negative statements heard from important people in the past that, when recalled in the present under stressful or uncertain conditions, painfully undermine beliefs in the capacity to make a decision [17,18].

RFT and ACT focus on analyzing the nature of human language and cognition and its application to understanding and alleviating suffering. Like CBT, ACT focuses on cognitions, behaviors, and emotions, especially those that are proximal to behavioral and emotional distress and actively cause behavioral and emotional distress [16]. As the third wave of behaviorism, the ACT advocates the openness and acceptance of psychological events, including those traditionally considered negative or irrational. The main purpose of the ACT is to encourage individuals to respond constructively to situations and to interact and accept challenging cognitive events, rather than to alter them [14]. One of the key features of ACT is its emphasis on this concept that behaviors and emotions can exist simultaneously and independently. ACT encourages the individual to accept life experiences that are challenging effective responses and to recognize and eliminate the controlling dimensions that specific contextual situations exert upon them [19]. ACT addresses psychological problems, including anxiety and depression, in the dynamic context of social, verbal, emotional, and other direct sensory effects on behavior with the primary goal of encouraging patients to look positively on life and accept negative experiences, including negative thoughts and feelings, as an integral part of life [9,20]. In the ACT, this success is obtained through increasing psychological flexibility.

In addition to acceptance, psychological flexibility also includes five other ket therapeutic processes: cognitive defusion, self-as-context, Contact with the present moment, values, and committed action. These six main processes of ACT are usually organized into what is called a "hex flex" (Figure 1).

Acceptance

In the ACT, acceptance (acceptance of unpleasant thoughts and feelings as they are) is defined as the desire to make room for and accept the inner unwanted experiences, not to fight against them, and avoid trying to change or eliminate them. Thus, acceptance is the opposite of empirical avoidance demonstrated by behaviors aimed at avoiding difficult thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations [21,22].

Cognitive defusion

In the ACT, Cognitive defusion is the process of retreating or detaching from useless thoughts and feelings to reduce their dominance over behaviors, which are taught through defusion techniques (metaphors, paradoxes, and empirical exercises). In this process, it is trying to look at useless thoughts and feelings as they are and not as unquestionable truths and reasons for action or inaction and to bring the individual’s behavior back to the control of unexpected events (the five senses) instead of control the language [9,21,22].

Contact with the present moment

In the ACT, contact with the present moment (conceptualized past and scary future) is the process of maintaining a connection with the present voluntarily and flexibly. This process refers to the psychological presence of what is happening here and now, being aware of and committing to what one is doing, rather than staying in a conceptualized past or being afraid of the future [9,23].

Self-as-context

Self-as-context (looking at thoughts and feelings without judgment) refers to the process of retreating from all definitions and stories about oneself, without disputing them, and trying to learn how to observe them [20-22].

Values

Values are desirable attributes toward constant action. In other words, values are those that one believes are important in different domains of his/her life beyond moral and ethical orders. This process aims to identify and link values to behaviors for making the right decisions and to pave the way for accepting life’s bitter experiences to provide a meaningful life for individuals [9,21].

Committed action

Committed action is about choosing a course of action guided by values and continuing in this choice, or changing directions if they are no longer useful [20]. In another word, it means doing whatever it takes to have a worthwhile life, even if it involves suffering [24].

ACT and anxiety and depression

Anxiety disorders: Evidence suggests that anxiety disorders are developed and maintained by avoidant behavior patterns and fusion with maladaptive thoughts. Research also indicates that attempting to regulate anxiety may increase psychological suffering and turn anxiety experiences into maladaptive forms. The ACT approach is well-tailored to address such concerns because it teaches individuals how to accept and deal with unpleasant symptoms of anxiety (e.g., worries, physical feelings, disturbing thoughts, etc.) instead of trying to eliminate or suppress them [25]. The ultimate aim of ACT for treating anxiety disorders is to help those individuals in treatment better deal with the anxiety experience (or related symptoms). Learning how to deal with these inner experiences (e.g., worry in Generalized Anxiety Disorders (GAD) and obsession in Obsessive- Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is not necessarily a means to reduce these experiences, but a process through which one can function better [15]. Thus, ACT enhances a desire to accompany all human experiences and consequently increases psychological flexibility and reduces attempts to avoid psychological and emotional phenomena [25].

Mixed anxiety

ACT has always been an integrated treatment protocol for issues where psychological inflexibility has been a major concern. Experimental evidence has shown the effectiveness of ACT in improving mixed anxiety in patients [15]. The results of the study by Ark et al. on the effectiveness of group-based ACT on mixed anxiety disorders in children showed the appropriateness of this treatment method in reducing mixed anxiety in children [26]. Similarly, Hancock et al. performed a study to evaluate the effectiveness of group-based ACT on mixed anxiety disorders in children. The results of their study also confirmed the effectiveness of ACT in the treatment of pediatric anxiety [13]. Similarly, Brem et al. stated in their study that the use of ACT for mixed anxiety reduces depressive symptoms and increases mindfulness and compassion [27]. Villatte et al. also indicated the use of ACT in the treatment of adults with mixed anxiety [28]. In all of these studies, there was a consensus that psychological flexibility as a process of change in ACT reduces anxiety and improves patients’ condition.

GAD

GAD is the most common anxiety disorder characterized by chronic and uncontrollable worry and is highly associated with other anxiety and depression disorders [25]. Several studies have shown the potential effectiveness of ACT in the treatment of GAD. In a study by Orsillo and Barlow they used acceptance- and value-based concepts inherent to ACT in the treatment of four patients with GAD. After a 10-week treatment period, two out of four patients showed a significant reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms and the third showed a slight improvement. The fourth patient missed several sessions and showed no improvement in symptoms. However, all participants reported significant and positive changes in their lives, especially regarding their jobs and relationships. They stated that the values and acceptance elements of treatment were very useful [29]. Ruiz et al. conducted a study to evaluate the effect of ACT protocol targeting Repetitive Negative Thinking (RNT) in the treatment of severe and comorbid anxiety and depression. In this study, six adult patients with at least one of the criteria for both the disorder and severe symptoms were included. Following the implementation of the ACT protocol, the follow-up showed significant clinical changes in five of the six participants. Finally, researchers concluded that the RNT-focused ACT protocol is effective in the treatment of severe GAD with depression and deserves further experiments [30]. In addition, similar results were reported by Wetherell et al. and Roberts et al. who indicated the effectiveness of ACT-based therapies in the treatment of patients with GAD [10,31].

Panic disorder

There are promising results in the treatment of panic disorder using ACT-based therapies. Lopez conducted a case study to evaluate the efficacy of ACT-based therapy in a male person suffering from panic disorder with agoraphobia. In this case study, the researcher reported that the patient completely recovered after twelve sessions of treatment [32]. Eifert et al. also conducted a case study, in which a 31-year-old man with an initial diagnosis of panic disorder was successfully treated using the ACT protocol [33]. Similarly, the results of a study by Ivanova et al., that examined the efficacy of the ACT-based application provided via the Internet in the treatment of panic disorder showed an improvement in the patients with this disorder [34].

Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD)

The results of the studies have indicated the potential of ACT as an effective treatment for SAD. Dalrymple and Herbert conducted a pilot study on 19 individuals with SAD over a 12-week program. The results of this study showed the acceptable and potential effectiveness of ACT for the treatment of SAD [35]. In two separate studies by Yuen et al. the researcher tested ACT-based therapy for SAD using a virtual environment and videoconferencing software [36,37]. The results of both studies clearly showed the improvement of SAD in the participants. In another study, Azadeh et al. examined the effectiveness of ACT-based protocols on interpersonal problems and the psychological flexibility of female high school students with SAD. The results showed that ACT-based therapy has a significant effect on interpersonal problems and their six dimensions as well as psychological flexibility [38].

OCD

OCD is the fourth most common psychiatric disorder worldwide with a prevalence of 1 to 3% in the general population [39]. As a new and effective intervention for OCD, ACT has attracted the attention of mental health professionals. Shabani et al. suggested that the use of ACT in adolescents with OCD leads to a significant improvement in psychological flexibility, mindfulness, and valuable life, and consequently a significant reduction in the severity of OCD [40]. Similarly, a recent systematic review examining the effectiveness of ACT in the treatment of OCD concluded that ACT significantly reduces the severity of symptoms in OCD [41].

Depressive disorders

Depressive disorders were one of the first clinical problems evaluated with ACT [15]. An individual with depressive disorder is surrounded by his/ her negative emotions and thoughts and tries to control or avoid them. In the ACT, this formulation changes to some extent, since changes in behavior may also change thoughts and feelings [42]. Similar to anxiety disorders, the goals of ACT to treat depression are not to eliminate depression itself, but to increase patients' engagement in effective and valuable activities in their lives [15]. The key point is to change behavior in such a way that the person takes a valuable path and moves towards his values despite negative thoughts and never gives up in dealing with problems. ACT somewhat diverges from behavioral activation and reflects traditional CBT in that a greater emphasis is posited on targeting cognitive and related psychological barriers that may hinder valuable action [15].

Fledderus et al. showed in their study that the application of ACT-based therapy significantly reduced depression in adults and the reduction in depressive symptoms maintained after a three-month follow-up period [43]. Similar results were reported by Hayes et al. in adolescents with severe depression [44]. Lappalainen et al. examined two ACT-based methods for treating depression including face-to-face and internet-based methods. The results of their study showed that both methods showed equal and high efficiency in the treatment of patients with depressive symptoms [45]. In another study, Walser et al. stated that the use of the ACT-based treatment method reduced depression and suicidal ideation in veterans [6]. In addition, Fernandez-Rodriguez et al. conducted a study to investigate the effectiveness of ACT on anxiety and depression in cancer survivors and reported an improvement in anxious and depressive levels in these patients [5]. In a similar study, Lawson et al. showed that the level of anxiety and depressive symptoms decreased in cancer survivors who underwent ACT after treatment [46]. In another study, Mihandost et al. examined the effectiveness of ACT-based education on psychological components in students. The results of their study showed a significant effect of ACT-based education on the levels of anxiety, depression, and stress in these students [47].

Conclusion

Based on the empirical evidence in the present study, it is well clear that ACT-based treatment protocols as a new generation of behavior therapy have attracted a lot of attention from therapists in recent years. The empirical evidence presented in this study supports the usefulness of ACT-based treatment protocols in the treatment of a range of anxiety and depression disorders. As explained, ACT employs various interventions and techniques to commit patients to pursue high quality, meaningful, and valuable life. By increasing psychological flexibility, ACT encourages patients to have a positive outlook toward their lives, to accept negative experiences, to deal with the present, and to adopt appropriate behaviors to cope with negative thoughts and feelings.

References

- A-tjak, Jacqueline GL, Michelle L Davis, Nexhmedin Morina and Mark B Powers, et al. “A Meta-analysis of the Efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Clinically Relevant Mental and Physical Health Problems.” Psychother Psychosom 84 (2015): 30-36.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Alavi, Zadeh Faranak and Atta Shakerian. “The Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Reducing Stress, Anxiety and Depression in Married Females Experiencing Infidelity (Emotional-Sexual).” Iran J Psych Nurs 4 (2017): 8-14.

- Fang, Shuanghu, Ding D. “A Meta-Analysis of the Efficacy of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Children.” J Contextual Behav Sci 15 (2020): 225-34.

- Davoudi, Mohammadreza, Amir Abbas Taheri, Ali Akbar Foroughi and Seyed Mojtaba Ahmadi, et al. “Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) on Depression and Sleep Quality in Painful Diabetic Neuropathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” J Diabetes Metab Disord 19 (2020): 1081-1088.

[Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Fernández-Rodríguez, Concepción, Sonia González-Fernández, Rocío Coto-Lesmes and Ignacio Pedrosa. “Behavioral Activation and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in the Treatment of Anxiety and Depression in Cancer Survivors: A Randomized Clinical Trial.” Behav Modif 45 (2021): 822-859.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Walser, Robyn D, Donn W Garvert, Bradley E Karlin and Mickey Trockel, et al. “Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Treating Depression and Suicidal Ideation in Veterans.” Behav Res Ther 74 (2015): 25-31.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Karlin, Bradley E, Robyn D Walser, Jerome Yesavage and Aimee Zhang, et al. “Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Depression: Comparison Among Older and Younger Veterans.” Aging Ment Health 17 (2013): 555-563.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Bluett, Ellen J, Kendra J Homan, Kate L Morrison and Michael E Levin, et al. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Anxiety and OCD Spectrum Disorders: An Empirical Review.” J Anxiety Disord 28 (2014): 612-624.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Li, Zhihong, Yanfei Li, Liping Guo and Meixuan Li, et al. “Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Mental Illness in Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Metaâ?ÂÂAnalysis of Randomised Controlled Trials.” Int J Clin Pract 75 (2021): e13982.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Wetherell, Julie Loebach, Lin Liu, Thomas L Patterson and Niloofar Afari, et al. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Older Adults: A Preliminary Report.” Behav Ther 42 (2011): 127-134.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Brzecka, Anna, Natalia Madetko, Vladimir N Nikolenko and Ghulam M Ashraf, et al. “Sleep Disturbances and Cognitive Impairment in the Course of Type 2 Diabetes-A Possible Link.” Curr Neuropharmacol 19 (2021): 78-91.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Davoudi, Mohammadreza, Abdollah Omidi, Mojtaba Sehat and Zahra Sepehrmanesh. “The Effects of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Man Smokers’ Comorbid Depression and Anxiety Symptoms and Smoking Cessation: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Addict Health 9 (2017): 129.

[Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Hancock KM, Swain J, Hainsworth CJ and Dixon AL, et al. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Versus Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Children with Anxiety: Outcomes of a Randomized Controlled Trial.” J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 47 (2018): 296-311.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Larmar, Stephen, Stanislaw Wiatrowski and Stephen Lewis-Driver. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: An Overview of Techniques and Applications.” J Ser Sci Mana 7 (2014): 1-2.

- Twohig, Michael P and Michael E Levin. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a Treatment for Anxiety and Depression: A Review.” Psychiatr Clin North Am 40 (2017): 751-770.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Hoare, P Nancey, Peter McIlveen and Nadine Hamilton. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) as a Career Counselling Strategy.” Int J Edu Voc Guide 12 (2012): 171-187.

- Hayes, Steven C. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Relational Frame Theory, and the Third Wave of Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.” Behavior Ther 35 (2004): 639-665.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Barnes-Holmes and Roche Bryan. Relational Frame Theory: A Post-Skinnerian Account of Human Language and Cognition. London, Kluwer Academic Plenum Publishers, UK (2001).

- Harris, Russell. “Embracing your Demons: An Overview of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.” Psychotherapy Aus 12 (2006): 1-2.

- Feliu-Soler, Albert, Francisco Montesinos, Olga Gutiérrez-Martínez and Whitney Scott, et al. “Current Status of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Chronic Pain: A Narrative Review.” J Pain Res 11 (2018): 2145.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Prevedini, Anna Bianca, Giovambattista Presti, Elisa Rabitti and Giovanni Miselli, et al. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): The Foundation of the Therapeutic Model and an Overview of its Contribution to the Treatment of Patients with Chronic Physical Diseases.” G Ital Med Lav Ergon 33 (2011): A53-63.

[Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Han, Areum, Hon K Yuen and Jeremy Jenkins. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Family Caregivers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” J Health Psychol 26 (2021): 82-102.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Gaudiano, Brandon A. “A Review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Recommendations for Continued Scientific Advancement.” Scientific Rev Mental Hea Pract 8 (2011): 5-22.

- Hayes, Steven C, Jacqueline Pistorello and Michael E Levin. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as a Unified Model of Behavior Change.” Counselling Psychol 40 (2012): 976-1002.

- Sharp, Katie. “A Review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy with Anxiety Disorders.” Int J Psychol Psychological Ther 12 (2012): 359-372.

- Arch, Joanna J, Georg H Eifert, Carolyn Davies and Jennifer C Plumb Vilardaga, et al. “Randomized Clinical Trial of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Versus Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for Mixed Anxiety Disorders.” J Consult Clin Psychol 80 (2012): 750.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Brem, Meagan J, Kristina Coop Gordon and Gregory L Stuart. “Integrating Acceptance and Commitment Therapy with Functional Analytic Psychotherapy: A Case Study of an Adult Male with Mixed Depression and Anxiety.” Clin Case Stud 19 (2020): 34-50.

- Villatte, Jennifer L, Roger Vilardaga, Matthieu Villatte and Jennifer C Plumb Vilardaga, et al. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Modules: Differential Impact on Treatment Processes and Outcomes.” Behav Res Ther 77 (2016): 52-61.

[Crossref] [Goggle Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Roemer, Lizabeth, and Susan M. Orsillo. “Expanding our Conceptualization of and Treatment for Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Integrating Mindfulness/Acceptance-Based Approaches with Existing Cognitive-Behavioural Models.” Clin Psychology: Sci Pract 9 (2002): 54.

- Ruiz, Francisco J, Carmen Luciano, Cindy L Flórez and Juan C Suárez-Falcón, et al. “A Multiple-Baseline Evaluation of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Focused on Repetitive Negative Thinking for Comorbid Generalized Anxiety Disorder and Depression.” Front Psychol 11 (2020): 356.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Roberts, Sarah L, and Ben Sedley. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy with Older Adults: Rationale and Case Study of an 89-year-Old with Depression and Generalized Anxiety Disorder.” Clin Case Stud 15 (2016): 53-67.

- López, Francisco and Javier Carrascoso. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) in Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia: A Case Study.” 4 (2000): 120-128. [Crossref]

- Eifert, Georg H, John P Forsyth, Joanna Arch and Emmanuel Espejo, et al. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Anxiety Disorders: Three Case Studies Exemplifying a Unified Treatment Protocol.” Cognitive and Behav Pract 16 (2009): 368-385.

- Ivanova, Ekaterina, Philip Lindner, Kien Hoa Ly and Mats Dahlin, et al. “Guided and Unguided Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder and/or Panic Disorder Provided via the Internet and a Smartphone Application: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” J Anxiety Disord 44 (2016): 27-35.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Dalrymple, Kristy L, and James D Herbert. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Generalized Social Anxiety Disorder: A Pilot Study.” Behav Modif 31 (2007): 543-568.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Yuen, Erica K, James D Herbert, Evan M Forman and Elizabeth M Goetter, et al. “Treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder using Online Virtual Environments in Second Life.” Behav Ther 44 (2013): 51-61.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Yuen, Erica K, James D Herbert, Evan M Forman and Elizabeth M Goetter, et al. “Acceptance Based Behavior Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder through Videoconferencing.” J Anxiety Disord 27 (2013): 389-397.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Azadeh SM, Kazemi-Zahrani H and Besharat MA. “Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Interpersonal Problems and Psychological Flexibility in Female High School Students with Social Anxiety Disorder.” Glob J Health Sci 8 (2016):131.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Philip, Joel and Vinu Cherian. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder: A Case Study.” Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine 44 (2021): 0253717621996734.

- Shabani, Mohammad Javad, Hamid Mohsenabadi and Abdollah Omidi, et al. “An Iranian Study of Group Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Versus Group Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Adolescents with Obsessive-compulsive Disorder on an Optimal Dose of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors.” J Obsessive-Compulsive Rel Dis 22 (2019): 100440.

- Philip, Joel and Vinu Cherian. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy in the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Systematic Review.” J Obsessive-Compulsive Related Dis 28 (2021): 100603.

- Hayes Steven C, Strosahl Kirk D. A Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. New York, Springer Science Business Media, USA (2005).

- Fledderus, M, Ernst Thomas Bohlmeijer, Marcel E Pieterse and Karlein Maria Gertrudis Schreurs. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy as Guided Self-help for Psychological Distress and Positive Mental Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” Psychol Med 42 (2012): 485-495.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Hayes, Louise, Candice P Boyd and Jessica Sewell. “Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Adolescent Depression: A Pilot Study in a Psychiatric Outpatient Setting.” Mindfulness 2 (2011): 86-94.

- Lappalainen P, Granlund A, Siltanen S and Ahonen S, et al. “ACT Internet-Based vs Face-to-Face? A Randomized Controlled Trial of Two Ways to Deliver Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Depressive Symptoms: An 18-month Follow-up.” Behav Res Ther 61 (2014): 43-54.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Lewson, Ashley B, Shelley A Johns, Ellen Krueger and Kelly Chinh, et al. “Symptom Experiences in Post-Treatment Cancer Survivors: Associations with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy Constructs.” Support Care Cancer 29 (2021): 3487-3495.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [Pubmed]

- Yravaisi, Fahimeh, Zainab Mihandoost and Shahram Mami. “The Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Based Education on Psychological Components (Stress, Anxiety, Depression) and Problem Solving Styles in First Secondary School Students in Sanandaj.” Edu Strategies Med Sci 14 (2021):12-22.

Citation: Isarizadeh, Motahhareh, Tahereh Sadeghiyeh, Seyedeh Sara Naghib Hosseini and Saeid Motevalli. “The use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Anxiety and Depression.” Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 16S (2022). DOI: 10.3371/CSRP.IMTS.011222.

Copyright: © 2022 Isarizadeh M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.