Research - Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses ( 2021) Volume 15, Issue 2

Shahram Vaziri, Department of Psychology, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran, Email: shahram.vaziri@gmail.com

Received: 28-Aug-2021 Accepted Date: Sep 08, 2021 ; Published: 15-Sep-2021

Abstract

Several factors can exacerbate emotional disorders and delay treatment and recovery. One of the most important life events affecting such disorders is the failure of a relationship and the consequent romantic breakup as a result of the emotional deviation from the natural path that can lead to other disorders and symptoms of complicated grief and sadness. Accordingly, the present study aimed to investigate the role of romantic breakup in exacerbating emotional disorders and intervening in treatment and recovery. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the role of romantic breakup in increased vulnerability toward a range of emotional disorders. In this systematic review, databases of Google Scholar, Science Direct, Web of Science and Pubmed were surfed to access English articles submitted between 2007 and 2021, and SID, Magiran and Ensani databases were surfed to explore Persian articles between 2013 and 2020. The results of the study showed that romantic breakup, experienced as a severe and traumatic stress, causes the experience of loss, affecting one’s expectation of the desired relationship as well as one’s assumptions about safety. As a result, the person experiences chronic feelings of emptiness and impatience, a lack of coherent sense of identity, as well as increased self-destructive behaviors and using ineffective coping strategies, higher psychological, emotional and physical distress, thus becomes more vulnerable to emotional disorders.

Keywords

Psychological • Relationship • Treatment

Introduction

In recent years, several models, especially cognitive and behavioral models, have developed to identify the underlying processes of disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [1]. However, some researchers have criticized such approaches, offering research- based classifications of mental disorders that are more empirical, one of which is the model of emotional disorders. The term "emotional disorders" refers to symptoms and disorders classified into the diagnostic categories of mood and anxiety disorders [2]. Accordingly, Watson introduced a category of emotional disorders for mood and anxiety disorders, which includes three subcategories: (i) turbulence and anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, general distress, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depressive mood), (ii) Bipolar disorder (cyclothymic, bipolar I and II), and (iii) panic disorders (panic, social phobias, specific phobias and transphobia). One of the reasons for using the concept of emotional disorders was the significant overlap between anxiety and mood disorders [3]. In this regard, integrative approaches consider emotional disorders as a continuum of psychiatric disorders caused by emotional dysregulation and dysfunction. Among their common features are coexistence [4,5], transdiagnostic causative factors and their effect on academic, occupational, and social functions [6,7]. Although unipolar mood and anxiety disorders are included in the continuum of emotional disorders [8], there was already evidence of classifying quasiphysical, dissociative and borderline personality disorders in the emotional disorders category in addition to mood and anxiety disorders [9]. Several studies have reported that failure in adaptive emotional experience is often attributed to psychological problems [10,11], which indicates the need for emotion regulation of individuals because it can play a protective role against emotional disorders [12].

Due to the high prevalence of emotional disorders, understanding the etiological factors of these disorders is of particular clinical importance. A number of causal factors have been suggested for these disorders, Including biological, genetic and environmental factors psychological factors, such as personality traits and sensitivity to anxiety and emotions and other factors including poverty, death or divorce of parents, a history of psychological illness in parents, low self-esteem, and chaotic family environment [13-18]. There is empirical evidence emphasizing the common features of major emotional disorders and many studies have indicated the overlap of these disorders throughout life [19-21]. On the other hand, due to the coexistence of a large number of emotional disorders and their consequences on individual and social functions, such disorders have received more and more attention. Considering the commonalities of such disorders and their affecting factors, it is possible to reduce costs and save time spent in the recovery process by facilitating the process of prevention, intervention and treatment [3].

One of the main consequences of mood disorders is affecting a person's relationship with others and consequently reducing the quality of communication argued in their research, such people complain of poor communication skills, because they receive lower acceptance from people around them and experience a variety of short-term and longlasting problems [22,23]. According to the related research [24,25], Some of the most important consequences of such relationships are academic, family, and job problems, psychological stress, etc. The importance of communication becomes clearer when considering the fact that one of the most important tasks of adulthood is choosing a spouse and establishing a pleasant and lasting relationship with the opposite sex. The ability to establish a lasting and meaningful relationship is regarded as one of the key social capacities of human beings because the need for love, affection and belonging are the most important human needs after physiological needs and security [26, 27]. In every period of life, a person is involved in special relationships with others that can promote his/her personal and social health or vice versa. Romantic relationships, especially in youth, are among important aspects of identity, social status, intimacy, and emotional security [28], so that the termination of such a relationship is an unpleasant event that anyone may experience in his/her life, because it’s negative consequences and feelings are inevitable. Due to the failure in love, the person experiences sadness, grief and isolation, called the state of frustration, which occurs after rejection by the beloved after intimacy [29]. Romantic breakup refers to a situation occurred after separation or failure of romantic relationships [30], which includes a set of severe signs and symptoms that appear after a breakup in a long-term romantic relationship and cause maladaptive reactions as well as dysfunction in various social, occupational and educational areas. Romantic breakup is experienced as severe and traumatic stress and causes psychological, emotional and physical distress in the person. Symptoms of romantic breakup increase after experiencing a love trauma because it violates the person’s favorable assumptions and expectations of the relationship and the presuppositions of his/her security in the relationship [31]. Thus, the person experiences it as a shocking event, which is often accompanied by feelings of panic, fear, and helplessness, which are similar to the situation that people experience in relation to death or threat of death [32]. This causes stress and a feeling of inability to control and prevent events [33]. In this regard, Saylor found that breakup of a relationship and romantic breakup are important life events with several negative consequences, including the occurrence of mood disorders and symptoms of complicated grief and sadness. Based on the theoretical hypothesis regarding the effect of romantic breakup on emotional disorders, we reviewed two perspectives and models on the effect of romantic breakup on vulnerability to emotional disorders.

A) Triple Vulnerability Model: It is one of the comprehensive models to explain the etiological factors of psychological disorders, which includes three types vulnerabilities: 1) general biological vulnerability, 2) general psychological vulnerability (perception of having low control over events, and 3) disorder-specific psychological vulnerability (derived from individual learning experiences) [34, 35]. The interaction between general biological and psychological vulnerabilities contributes to moods that are likely to lead to emotional disorders [36]. In addition, a specific type of disorder-specific psychological vulnerability is related to disorders such as thought-action fusion in obsessive-compulsive patients [37], low anxiety control in patients with generalized anxiety disorder, major depression, and obsessive- compulsive disorder [38]. There are also relations between dysfunctional attitudes with depression, thought-action fusion with obsession, and intolerance of uncertainty with widespread anxiety [39-42]. Based on this model, the desire to underestimate capabilities and react to intense emotions, self-criticism in stressful situations, and the desire to experience less positive emotions, causes people to react more negatively to unpleasant stimuli. As a result, the susceptibility to unpleasant experiences increases, which in turn increases their psychological problems. In this model, it is believed that there is a pronounced feeling of uncontrollability, especially when people face tasks or challenges that may be threatening [9], thus, feeling of failure or weakness is a sign of chronic disability while dealing with negative events that are unpredictable and uncontrollable, leading to a feeling of uncontrollability and negative emotions [11]. Feeling of uncontrollability is widely associated with negative emotional response capacity. Low perception and unpredictability have a direct impact on bio-vulnerability and especially play an important role in increasing HPA- based activity which is considered as a key factor in reacting to stressful events. In addition, it involves different parts of the brain associated with emotional disorders. Thus, it is conceivable how interactions between general biological and psychological factors make individuals vulnerable to emotional disorders. In this sense, the experience of romantic breakup can cause feelings of uncontrollability and the spread of negative emotions, and as a result, make a person vulnerable to emotional disorders. In the case of disorder-specific psychological vulnerability, it can be argued that dysfunctional attitudes acquired by experiencing romantic breakup in the vulnerable person towards themselves and the world, causing the person to interpret specific facts too negatively and inefficiently, and this contributes to emotional disorders, especially depression. In other words, the presence of negative, inflexible, perfectionist and inefficient attitudes towards self/ others and the future, as they are non-standard and unrealistic, causes negative mood, reduced pleasure and interest and at last, depression in these people, thus, make them more vulnerable to other emotional disorders. On the other hand, it has been argued that by creating a state of uncertainty, romantic breakup causes a person to have a strong tendency to threateningly interpret vague information, which may increase anxiety and worry about the interpretation of concepts arising from emotional situations, and by increasing negative emotional experiences, provide the ground for psychological disorders.

B) Diathesis- Stress Model: This model describes the complex interaction between genes and the environment of psychological vulnerability in detail and shows the important role of this relationship in the development of mental disorders [43]. Emphasizing the interaction between disease preparedness and environmental disturbances, this model states that those who are genetically vulnerable to physical and mental problems are more vulnerable to psychological disorders when placing in stressful situations. Vulnerability is a predisposing factor for the emergence of disorders and incompatibilities, having a number of symptoms including situational symptoms, personality traits, or external sources such as poor social support [44]. In addition to innate readiness for disease, disease preparedness includes other characteristics that increase the risk of a disorder in the individual. Stress, on the other hand, refers to major traumatic events and increased chronic events [45]. Generally, this model states that having preparedness disease to a disorder alone does not necessarily lead to a disorder; however, it increases the risk of developing the disorder. In other words, the presence of a specific vulnerability does not necessarily mean the occurrence of a disorder, but requires a larger stressful event in the life of a person with minor vulnerability. Conversely, in the case of high vulnerability, even a minor stress can lead to the disorder. Therefore, this model considers the stress and disease preparedness as harmful or unpleasant environmental stimuli that trigger the psychological damage. According to this model, romantic breakup is a traumatic event that significantly increases the incidence of psychological and emotional disorders by increasing the individual's vulnerability to emotional disorders.

Methodology

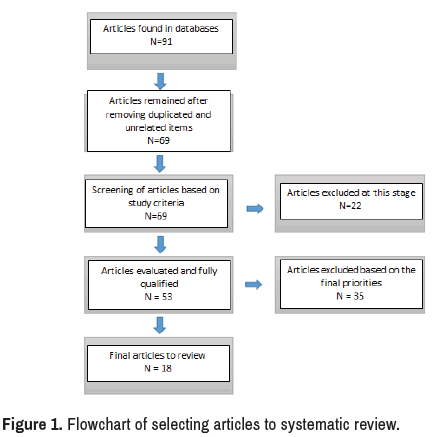

This study is a systematic review of articles examining the impact of romantic breakup on vulnerability to emotional disorders, which were published from 2004 to 2021. In order to collect data, international databases such as Google Scholar, Science Direct, Web of Science and Pubmed, and Iranian databases including SID, Magiran and Ensani were employed and English keywords of love trauma, vulnerability and emotional disorders were used to access the related articles (Figure 1).

Article selection and data extraction: First, articles and researches related to the subject were explored using the above-mentioned keywords and then, a list of articles on romantic breakup and vulnerability to emotional disorders along with their abstracts was prepared and added to the initial list. Next, a checklist of information required in the study including research location, year of publication, methodology, number of samples, sampling method and data collection tool was prepared and after reviewing by the researcher, related articles were selected and included in the review. The initial search using the above-mentioned keywords resulted in 91 articles, of which 69 records remained after the necessary screening and excluding unrelated articles. In the next step, the abstracts of the selected articles were studied and 53 articles were selected, all of which were exclusively related to the subject of the study. Finally, after excluding duplicated and similar studies and considering the priority of publication year, 18 articles were included in the study in line with the purpose of the research. Inclusion criteria were research-related studies, newly released studies and nonduplicated studies, while exclusion criteria were unrelated or less relevant studies, studies published outside the specified range, and studies with duplicated topics.

Results

After screening and evaluating the explored articles, 18 articles were finally selected for the review. These studies were conducted in the United States, Canada, the Netherlands, Australia, Austria, Italy, and Iran, and include the following topics: the phenomenological study of romantic breakup, the role of protective and traumatic factors, its relationship with suicide and exacerbation of other disorders, its effects on other mental health variables, its relationship with influential variables during the treatment process, and other disorders such as bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. The total number of participants in the study was 20,251. A summary of the systematic review findings is provided in Table 1.

| Author/ year/ country |

Title | Methodology | Number of samples and sampling method | Data collection tools | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sailor/2013/USA | A Phenomenological Study of Falling Out of Romantic Love | Moustakas phenomenological method | N=8 Convenience sampling |

Interview | As the main factors of terminating an emotional relationship, loss of trust, intimacy and feeling loved, emotional pain and negative self-esteem cause a person to become more vulnerable and lead to several negative consequences, including mood disorders and symptoms of complicated grief and sadness. |

| Ratto/2007/Canada | The role of attachment style with mother and father in adolescents' ways of coping with a romantic break up | Regression | N=51 Convenience sampling |

Romantic breakup coping questionnaire (Volkman and Lazarus, 1985) and Attachment questionnaire (Brennan, Clark & Shaver, 1998) | Attachment to mother is important in the development of coping strategies for emotional regulation in romantic relationships and has a positive relationship with the coping method with romantic breakup and some of these relationships are mediated by the stress. Romantic breakup is considered as one of the main predictors of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. |

| Sewall et al./2020/USA | Interpersonal relationships and suicidal ideation in youth with bipolar disorder | Regression | N=404 Convenience sampling |

psychosocial functioning questionnaire (keller et al. 1987); Depression part of the K-SADS-PL Program (Kaufman et al., 1997) |

36% of the sample reported suicidal ideation and significantly worse family/peer relationships during the disorder, and there was a relationship between family/peer relationships and suicidal ideation. Bipolar patients are weak in forming and maintaining intimate relationships and expressing intimacy, making them more vulnerable to relationship breakdown and romantic breakup, causing them to experience the symptoms of the disorder more severely. |

| Verhallen et al./2019/Netherlands | Romantic relationship breakup: An experimental model to study effects of stress on depression symptoms | Experimental study | N=107 Convenience sampling |

Questionnaires of major depression (Beck et al., 2001), complicated grief (Prigerson et al., 1995), positive and negative emotion (Watson et al., 1988), components of perceived relationship quality (Fletcher, Simpson, & Thomas, 2000) and passionate love (Hotfield and Spracher, 1986) | As a stressor, romantic relationship breakup plays an aggravating role in increasing the severity of depression and makes the patients more vulnerable compared to compared to those without a history of depression. |

| Smyth et al./2021/USA | Interpersonal functioning, support, and change in early-onset bipolar disorder: a transcendental phenomenological study of emerging adults | qualitative phenomenological approach | N=8 Purposive sampling |

Semi-structured interview | Due to the simultaneous and continuous challenges in symptom management, maintaining social, occupational, educational performance and simultaneous changes in family and romantic relationships, the experience of romantic breakup in adolescent and young bipolar patients leads to a loss of capacity for behavioral change and cessation of participatory processes, communication and cohesion, and reduced participation of family members, all of which can reduce the level of support received by a person, making him/her more vulnerable to other emotional disorders. |

| Slotter et al./2010/USA | Who am I without you? The influence of romantic breakup on the self-concept | Regression | N=72 Convenience sampling |

Self-concept clarity scale (Campbell et al., 1996) | As partners develop a shared self-concept, this intertwining of selves may leave individuals’ self-concepts vulnerable to change after an emotional breakdown and reduce the clarity of the self-concept, which is a predictor of post-collapse emotional distress. |

| Green et al./2010/Australia | Cognitive regulation of emotion in bipolar I disorder and unaffected biological relatives | causal-comparative | N=282 Convenience sampling |

Questionnaires of cognitive emotion regulation (Garnefski et al., 2006), Depression, Anxiety and Stress (Lavibond and Lavibond, 1995), Hypomanic Personality Scale (Eckblad and Chapman, 1986) | Due to more frequent use of maladaptive strategies such as rumination, catastrophizing and self-blame, and less frequent use of adaptive strategies such as putting into perspective, patients with type 1 bipolar disorder experienced more negative consequences in long-term in response to negative life events such as romantic breakup, making them more vulnerable to other disorders. |

| MacDonald et al./2016/USA | Love, trust, and evolution: Nurturance/love and trust as two independent attachment systems underlying intimate relationships | Regression | N=635 Cluster sampling |

Interpersonal Adjective Scale (Trapnell and Wiggins, 1990), experiences in close relationships questionnaire (McDonald, 1992), Avoidance Attachment Style Questionnaire (Fraley et al., 2000) | There is a significant negative relationship between love and avoidant attachment style. |

| Yarnell & Neff/2013/USA | Self-compassion, interpersonal conflict resolutions, and well-being | Regression | N=506 Convenience sampling |

Self-Compassion (Neff, 2003), Conflict Resolution Behavior (Neff and Harter, 2002), Welfare (Harter et al., 1992) | Romantic breakup causes clinical symptoms by creating conflict and confusion in the relationship. People with high self-compassionate are more likely to resolve their relationship conflicts with their partners using compromised solutions. Even if they fail in a romantic relationship, high self-compassion will help them not to get turmoil and find a better way to deal with the situation instead of showing clinical symptoms. |

| Till et al./2016/Austria | Relationship satisfaction and risk factors for suicide | causal-comparative | N=382 Random sampling |

Relationship Assessment Scale (Hendrick, 1988), Suicide Probability Scale (Cull and Gill, 1988), Hopelessness Scale (Beck et al., 1988), Erlanger Depression Scale (Lehrl et al., 1983) | Participants reporting a high number of unsolved con�icts in their relationship had higher levels of suicidal ideation, hopelessness, and depression than individuals who tend to solve issues with their partner amicably or report no con�icts. |

| Schmitt et al./2009/International | When will I feel love? The effects of culture, personality, and gender on the psychological tendency to love | Modeling | N=15234 Convenience sampling |

5 Factor model of personality questionnaire (Benet-Martinez and John, 1998), Relationship questionnaire (Barselomio and Horowitz, 1991), Self-Esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965), Gender Attitudes (Schmitt & Boss, 2000) | An romantic breakup triggers stress and makes the person feel unable to control and prevent events, and the person may engage in risky behaviors such as self-harm or suicide. |

| Cerutti et al./2018/Italy | The role of difficulty in identifying and describing feelings in non-suicidal self-injury behavior (NSSI): associations with perceived attachment quality, stressful life events, and suicidal ideation | Modeling | N=700 Convenience sampling |

Self-harm questionnaires (Graz, 2001), suicidal ideation (Kovacs, 2015), emotional malaise (Riff et al., 2006), parental attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) and life stressors checklist (Wolfe et al., 1996) | Emotional trauma reduces the ability to resist negative emotions. Coping strategies employed by a person against negative emotions are more likely to increase his/her vulnerability to suicide. Thus, emotional trauma causes long-term maladaptive behaviors that negatively affects the mood, and can increase vulnerability to emotional disorders and ultimately lead to suicidal ideation. |

| Sbarra et al./2012/USA | When leaving your ex, love yourself: Observational ratings of self-compassion predict the course of emotional recovery following marital separation | Regression | N=109 Purposive sampling |

Self-Compassion Scale (Raes et al., 2011), Impact of Event Scale-Revised (Weiss and Marmar, 1997) | People failing in their romantic relationships experience extreme sadness, depression, loss of self-confidence and self-esteem, and increase their negative emotions by criticizing themselves. |

| Simon & Barrett/2010/USA | Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood | causal-comparative | N=1683 Purposive sampling |

Depression Scale (Radloff, 1977), Abuse / Dependence Scale (Aseltyne & Gar, 2005) | Emotionally, romantic breakup leads to apathy of people, which is associated with a decrease in their well-being. |

| Ghazinejad et al./2020/Iran | Explanation of Cognitive Reactions in Girls with Love Trauma Syndrome: A Phenomenological Study. | qualitative phenomenological approach | N=14 Purposive sampling |

Semi-structured interview | The main theme of "cognitive maladaptive reactions" includes sub-themes of 1) disorientation, 2) maladaptive decision-making, 3) Bargaining, 4) changed beliefs, 5) cognitive distortions, and 6) Rumination. |

| Asayesh et al./2020/Iran | Explanation of emotional Reactions in Girls with Love Trauma Syndrome: A Phenomenological Study | qualitative phenomenological approach | N=14 Purposive sampling |

Semi-structured interview | The main theme was "maladaptive emotional reactions" which included the sub-themes "feeling of failure, feelings of worthlessness, emotional confusion, fear, inadequacy and grief, vulnerability, depression, anger, jealousy, boredom, unwillingness, frustration and hatred”. |

| Karaminezhad et al./2017/Iran | Effectiveness emotion focused therapy approach on cognitive emotion regulation on emotional breakdown girl students | Semi-experimental | N=22 Convenience sampling |

Love Trauma Questionnaire (Rosse, 1999); Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (Garnefski et al., 2006) | The emotion-focused approach in the post-test and follow-up stages has provokrd more positive strategies for cognitive emotion regulation in the experimental group compared to the control group. Since love and feelings associated with love trauma are classified under the category of emotions, the emotionally-focused therapy can have a significant effect on the cognitive regulation of emotion in female students with love trauma. |

| Riahinia et al./2013/Iran | Comparing the effectiveness of bibliotherapy and cognitive behavior therapy on the depression of undergraduate students with emotional trauma | Semi-experimental | N=20 Convenience sampling |

Depression questionnaire (Beck, 1991) | People without a deep emotional experience and secure attachment in the family are more likely to experience psychological breakdown after emotional trauma. |

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the role of romantic breakup in increasing vulnerability to emotional disorders. For this purpose, 18 scientific articles related to the research topic were selected and separately reviewed. The following is the summary of the study.

According to the triple vulnerability model, the occurrence of disturbing thoughts, doubts, emotions and feelings are considered as threatening when they lead to the emergence of metacognitive beliefs about their importance and meaning. These beliefs include thought-event fusion and thought-action fusion [46]. Such metacognitive processes may be perceived as a sign of danger by the individual. In addition, a negative evaluation of such thoughts causes a person to experience intense negative emotions, especially anxiety, anger, and guilt, causing him/her to experience more disturbing thoughts and feelings in a vicious cycle. As a result, special strategies such as ritual beliefs, neutralization, thought suppression, mental arguing, verification, etc. might be employed to deal with the perceived danger. Since such rules are unrealistic and psychologically require a lot of energy to be achieved, they cause stress and tension, preventing the realistic evaluation of these disturbing thoughts and feelings in the mind. As a result, perceptions of danger and negative emotions persist. In other words, such metacognitive and ritual beliefs lead to the formation of dysfunctional behaviors that may last for hours and, thus, deprive a person of the possibility to perform a realistic evaluation of intellectual content and ritual behaviors, causing intensified and perpetuated negative moods and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, which may eventually lead to emotional disorders. As romantic breakups are stressor events, they increase anxiety in the individual. Based on the anxiety tolerance model, such people perceive romantic breakup as turmoil events and will ultimately experience chronic anxiety in response to such situations. Based on the anxiety tolerance model, being anxiety will help such people to deal effectively with ambiguous frightening situations, thereby preventing the occurrence of adverse events. Self-concern leads to negative bias and cognitive avoidance toward emotional trauma, causes persistent anxiety in a vicious cycle. While rejecting the existence of possible ambiguous situations, they use anxiety as the main strategy to reduce their levels of intolerance when facing such situations, indicating that there is a strong relationship between anxiety and intolerance. In the above process, therefore, the person is more vulnerable to emotional disorders due to the experience of chronic anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty.

The vulnerability-stress model states that high levels of anxiety are a risk factor for extreme reactions to stress as well as vulnerability to mental disorders, especially emotional disorders [47]. People with high levels of anxiety overreact to threatening romantic breakups and ambiguous stimuli [48-53]. Therefore, such people are more vulnerable to stress-induced changes. On the other hand, increased sensitivity to threats combined with annoying and negative thoughts neutralizes people's responses to major stressors in their lives. Finally, negative emotions reinforce the main features of emotional disorders such as emotional dysregulation, mood swings, frustration, helplessness, worthlessness, and lack of pleasure, and contribute to the occurrence and progression of such disorders in other words, increased sensitivity to threats combined with annoying and negative thoughts neutralizes people's responses to major stressors in a vicious cycle, which ultimately reinforce the main features of emotional disorders and contribute to the occurrence and progression of emotional disorders. Although emotions help us to provide an adaptive respond to opportunities and threats, their deviation from original path can increase our vulnerability to emotional disorders. In this regard, romantic breakup or love trauma syndrome has four basic characteristics, including "arousal, avoidance, automatic remembering and emotional anaesthesia" [54-60], which can cause emotions to deviate from their original path by interfering with the process of emotional regulation. Thus, it is more likely to use ineffective coping strategies when facing stressful events after a romantic breakup. On the other hand, since love trauma syndrome are divided into two categories, including type I (sudden and unexpected events, during which the person feels completely defeated) and type II (repetitive and chronic events, during which a person's desirable expectations of the relationship are constantly shattered) it can be found that both types can reduce the coping ability and increase avoidance strategies of a person that prevent correctional learning in him/her. Such people may also complain of chronic feelings of emptiness, impatience, and lack of perceived identity, and when pressured, complain of being very depressed most of the times despite the intense expression of emotional states. On the other hand, they may often try to compensate for the love trauma with an alternative and avoid the resulting emotional pain [61-65].They may be relatively successful in the short term, but they are always at risk of suppressing consequences of love trauma syndrome, in which case a more complicated syndrome is more likely. Manifestations of such an event can be in the form of changing attitudes, especially towards the opposite sex with hatred, avoidance of communication, aggression, and childish and immature personality behaviors, which ultimately lead to self-destructive behaviors in such people. This paves the way for greater vulnerability to other emotional disorders by reducing psychological and behavioral capacity of the individual to cope with stressful situations [66-72].

Conclusion

Romantic breakup refers to a situation occurred after separation or failure of romantic relationships, which includes a set of severe signs and symptoms that appear after a breakup in a long-term romantic relationship and cause maladaptive reactions as well as dysfunction in various social, occupational and educational areas. Romantic breakup is experienced as severe and traumatic stress and causes psychological, emotional and physical distress in the person. Symptoms of romantic breakup increase after experiencing a love trauma because it violates the person’s favorable assumptions and expectations of the relationship and the presuppositions of his/her security in the relationship. Thus, it is more likely to use ineffective coping strategies when facing stressful events after a romantic breakup.

References

- Wigman, JT, J Van Os, D Borsboom and KJ. Wardenaar, et al. “Exploring the Underlying Structure of Mental Disorders: Cross-Diagnostic Differences and Similarities from a Network Perspective Using both a Top-Down and a Bottom-up Approach.” Psychol Med 45 (2015): 2375-2387.

- Rosellini, AJ. Initial Development and Validation of a Dimensional Classification System for the Emotional Disorders. Boston University, USA, (2013).

- Kessler, Ronald C, Shelli Avenevoli, Jane Costello and Jennifer Greif Green, et al. “Severity of 12-month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement.” Arch Gen Psychiatry 69 (2012): 381-389.

- Power Mick and Dalgleish Tim. Cognition and Emotion: From Order to Disorder. Psychology Press: London, UK (2015).

- Spinhoven, Philip, Jolijn Drost, Mark de Rooij and Albert M van Hemert. et al. “A Longitudinal Study of Experiential Avoidance in Emotional Disorders.” Behav Ther 45 (14): 840-850.

- Krueger, Robert F and Nicholas R Eaton. “Transdiagnostic Factors of Mental Disorders.” World Psychiatry 14 (2015): 27.

- Ehring, Thomas, Ulrike Zetsche, Kathrin Weidacker, Karina Wahl, Sabine Schönfeld, and Anke Ehlers. “The Perseverative Thinking Questionnaire (PTQ): Validation of a Content-Independent Measure of Repetitive Negative Thinking.” J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 42 (2011): 225-232.

- Zvolensky, Michael J, Lorra Garey and Jafar Bakhshaie. “Disparities in Anxiety and its Disorders.” J Anxiety Disord (2017): 1-5.

- Barlow, David H. Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders: A Step-by-Step Treatment Manual. New York: Guilford Press, USA, (2004).

- De Berardis, Domenico, Michele Fornaro, Laura Orsolini and Antonio Ventriglio, et al. “Emotional Dysregulation in Adolescents: Implications for the Development of Severe Psychiatric Disorders, Substance Abuse, and Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors.” Brain Sci 26(2020): 591.

- Paulus, Daniel J, Salome Vanwoerden, Peter J Norton and Carla Sharp. “Emotion Dysregulation, Psychological Inflexibility, and Shame as Explanatory Factors between Neuroticism and Depression.” J Affect Disord 190 (2016): 376-385.

- Bayes, Adam, Gordon Parker, and Georgia McClure. “Emotional Dysregulation in Those with Bipolar Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder and their Comorbid Expression.” J Affect Disord 204 (2016): 103-111.

- Hettema, John M, Carol A Prescott, John M Myers and Michael C Neale, et al. “The Structure of Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Anxiety Disorders in Men and Women.” Arch Gen Psychiatry 62 (2005): 182-189.

- Vink, Dagmar, Marja J Aartsen and Robert A Schoevers. “Risk Factors for Anxiety and Depression in the Elderly: A Review.” J Affect Disord 106 (2008): 29-44.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC, USA, (2021).

- Leahy, L Robert, Holland, Stephen, and, Lata K McGinn. Treatment plans and interventions for depression and anxiety disorders. Guilford Press: New York City, (2011).

- Zhang, X, J Norton, I Carriere and K Ritchie. et al. “Risk Factors for Late-Onset Generalized Anxiety Disorder: Results From a 12-Year Prospective Cohort (The ESPRIT Study).” Transl Psychiatry 5 (2015): e536-e536.

- Blanco, Carlos, José Rubio, Melanie Wall and Shuai Wang, et al. “Risk Factors for Anxiety Disorders: Common and Specific Effects in a National Sample.” Depress Anxiety 31 (2014): 756-764.

- Brown, Timothy A, and David H Barlow. “A Proposal for a Dimensional Classification System Based on the Shared Features of the DSM-IV Anxiety and Mood Disorders: Implications for Assessment and Treatment.” Psychol Assess 21 (2009): 256.

- Boettcher, Hannah, Jeannette Correa, Clair Cassiello-Robbins and Amantia Ametaj, et al. “Dimensional Assessment of Emotional Disorder Outcomes in Transdiagnostic Treatment: A Clinical Case Study.?” Cognitive Behav Practice 27 (2020): 442-453.

- Brown, Timothy A, Laura A Campbell, Cassandra L Lehman and Jessica R Grisham, et al. “Current and Lifetime Comorbidity of the DSM-IV Anxiety and Mood Disorders in a Large Clinical Sample.” J Abnorm Psychol 1100020 (2001): 585.

- Beidel, Deborah C, Candice A Alfano, Michael J Kofler and Patricia A Rao, et al. “The Impact of Social Skills Training for Social Anxiety Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” J Anxiety Disord 28 (2014): 908-918.

- Kupferberg, Aleksandra, Lucy Bicks, and Gregor Hasler. “Social Functioning in Major Depressive Disorder.” Neurosci Biobehav Rev 69 (2016): 313-332.

- Bowie, Christopher R, Michael W Best, Colin Depp and Brent T Mausbach, et al. “Cognitive and Functional Deficits in Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia as a Function of the Presence and History of Psychosis.” Bipolar Disord 20 (2018): 604-613.

- Stravynski, Ariel, Kyparissis Angela, and Amado Danielle. Social Phobia as a Deficit in Social Skills. In Social anxiety Academic Press: USA, (2011).

- Thimm, Jens C. “Relationships Between Early Maladaptive Schemas and Psychosocial Developmental Task Resolution.” Clin Psychol Psychother 17 (2010): 219-230.

- Hopper, Elizabeth. “Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Explained.” Viitattu 12 (2019): 1-2.

- Sailor, Joanni L. “A Phenomenological Study of Falling Out of Romantic Love.” Qualitative Rep 18 (2013): 37.

- Rosse, RB. The love trauma syndrome: free yourself from the pain of a broken heart. Da Capo Lifelong Books, USA, (2007).

- Chatav, Yael, and Mark A Whisman. “Partner Schemas and Relationship Functioning: A States of Mind Analysis.” Behav Ther 40 (2009): 50-56.

- Dehghani, Mahmood, Mohammad-Kazem Atef-Vahid and Banafsheh Gharaee. “Efficacy of Short–Term Anxiety-Regulating Psychotherapy on Love Trauma Syndrome.” Iranian journal of psychiatry and behavioral sciences 5 (2011): 18.

- Rosse, B Rosse. The Love Trauma Syndrome: Free Yourself from the Pain of a Broken. USA, (1999).

- Schmitt, David P, Gahyun Youn, Brooke Bond and Sarah Brooks et al. “When Will I Feel Love? The Effects of Culture, Personality, and Gender on the Psychological Tendency to Love.” J Res Person 43 (2009): 830-846.

- Barlow, David H. “Unraveling the Mysteries of Anxiety and its Disorders from the Perspective of Emotion Theory.” Am Psychol 55 (2000): 1247.

- Allen, Laura B, Kamila S White, David H Barlow and M Katherine Shear, et al. “Cognitive-Behavior Therapy (CBT) for Panic Disorder: Relationship of Anxiety and Depression Comorbidity with Treatment Outcome.” J Psychopathol Behav Assess 32 (2010): 185-192.

- Barlow, David H. Anxiety and its disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety and Panic. New York: Guilford Press, USA, (2004).

- Suárez, Liza M, Shannon M Bennett, Clark R Goldstein and David H Barlow. “Understanding Anxiety Disorders from a" Triple Vulnerability" Framework." 25 (2009) 153-172.

- Brown, Timothy A, and Kristin Naragon-Gainey. “Evaluation of the Unique and Specific Contributions of Dimensions of the Triple Vulnerability Model to the Prediction of DSM-IV Anxiety and Mood Disorder Constructs.” Behav Ther 44 (2013): 277-292.

- Cowie, Jennifer, Michelle A Clementi, and Candice A Alfano. “Examination of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Construct in Youth with Generalized Anxiety Disorder.” J Clin Child Adolesc Psycho 47 (2018): 1014-1022.

- Jones, Rhiannon and Joydeep Bhattacharya. “A Role for the Precuneus in thought–Action Fusion: Evidence from Participants with Significant Obsessive–Compulsive Symptoms.” Neuro Image Clinical 4 (2014): 112-121.

- Thomas, Justin, and Belkeis Altareb. “Cognitive Vulnerability to Depression: An Exploration of Dysfunctional Attitudes and Ruminative Response Styles in the United Arab Emirates.” Psychol Psychother 85 (2012): 117-121.

- Anderson, Kristin G, Michel J Dugas, Naomi Koerner, and Adam S Radomsky, et al. “Interpretive Style and Intolerance of Uncertainty in Individuals with Anxiety Disorders: A Focus on Generalized Anxiety Disorder.” J Anxiety Disord 26 (2012): 823-832.

- Barlow, David H. and Durand, VM. Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach: Nelson Education. Ontario: Toronto, Canada, (2011).

- Goetzmann, Lutz, Richard Klaghofer, Regula Wagner-Huber and Jörg Halter et al. “Psychosocial Vulnerability Predicts Psychosocial Outcome after an Organ Transplant: Results of a Prospective Study with Lung, Liver, and Bone-Marrow Patients.” J Psychosomatic Res 62 (2007): 93-100.

- Kring, AM, Johnson, SL, Davison and Neale JM. Abnormal Psychology Eleventh Edition. Asia: John Wiley and Sons: US, (2010).

- Wells, Adrian, and Robert L. Leahy. “Cognitive Therapy of Anxiety Disorders: A Practice Manual and Conceptual Guide.” 5 (1998): 350-353.

- Rogers, JM, Raveendran, GL Fawcett, AS Fox and SE Shelton, et al. “CRHR1 Genotypes, Neural Circuits and the Diathesis for Anxiety and Depression.” Mol Psychiatry 18 (2013): 700-707.

- Bishop, Sonia J. “Neurocognitive Mechanisms of Anxiety: An Integrative Account.” Trends Cogn Sci 11 (2007): 307-316.

- Sandi, Carmen and Gal Richter-Levin. “From High Anxiety Trait to Depression: A Neurocognitive Hypothesis.” Trends Neurosci 32 (2009): 312-320.

- Stuijfzand, Suzannah, Cathy Creswell, Andy P Field and Samantha Pearcey et al. “Research Review: Is Anxiety Associated with Negative Interpretations of Ambiguity in Children and Adolescents? A Systematic Review and Metaâ?Analysis.” J Child Psychol Psychiatry 59 (2018): 1127-1142.

- Gilbert, Steven P and Sarah K Sifers. “Bouncing Back from a Breakup: Attachment, Time Perspective, Mental Health, and Romantic Loss.” J College Student Psycho 25 (2011): 295-310.

- Fisher, Helen E. “The Tyranny of Love: Love Addiction—an Anthropologist’s View.” Behav Addiction 5 (2014): 237-265.

- Winborn, Mark. Shared Realities: Participation Mystique and Beyond. Fisher King Press, USA, (2014).

- Asayesh, Mohammad Hassan, Ghazinejad Niku, Bahonar and Fahima. “Explanation of Cognitive Reactions in Girls with Love Trauma Syndrome: A Phenomenological Study. Women and Families Journal 15 (2020): 154-125.

- Explanation of Cognitive Reactions in Girls with Love Trauma Syndrome: A Phenomenological Study

- Ghazinejad, Nikoo, Mohammad Hassan Asayesh, and Fahime Bahonar. “Explanation of Cognitive Reactions in Girls with Love Trauma Syndrome: A Phenomenological Study." Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi J 9 (2020): 97-106.

- Karaminezhad, Zeynab and Mansour Sodani. “Effectiveness Emotion Focused Therapy Approach on Cognitive Emotion Regulation on Emotional Breakdown Girl Students.” Yafteh 18 (2017): 79-86.

- Riahinia, Nosrat, Valiollah Farzad, Nasrin Haseli and Maryam Emami. “Comparing the Effectiveness of Bibliotherapy and Cognitive Behavior Therapy on the Depression of Undergraduate Students with Emotional Breakdown.” J Academic Librarian Information Res 48 (2015): 501-514.

- Cerutti, Rita, Antonio Zuffianò and Valentina Spensieri. “The Role of Difficulty in Identifying and Describing Feelings in Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Behavior (NSSI): Associations with Perceived Attachment Quality, Stressful Life Events, and Suicidal Ideation.” Front Psychol 9 (2018): 318.

- Carl, Jenna R, David P Soskin, Caroline Kerns and David H Barlow. “Positive Emotion Regulation in Emotional Disorders: A Theoretical Review.” Clin Psychol Rev 33 (2013): 343-360.

- Green, MJ, BJ Lino, EJ Hwang and A Sparks et al. “Cognitive Regulation of Emotion in Bipolar I Disorder and Unaffected Biological Relatives.” Acta Psychiatr Scand 124 (2011): 307-316.

- MacDonald, Kevin, Emily Anne Patch and Aurelio José Figure do. “Love, Trust, and Evolution: Nurturance/Love and Trust as Two Independent Attachment Systems Underlying Intimate Relationships.” Psychology 7 (2016): 238.

- Ratto, Nicolina. “The Role of Attachment Style with Mother and Father in Adolescents' Ways of Coping with a Romantic Break up.” Concordia University 5 (2007): 1-2.

- Paulus, Daniel J, Salome Vanwoerden, Peter J Norton and Carla Sharp. “From Neuroticism to Anxiety: Examining Unique Contributions of Three Transdiagnostic Vulnerability Factors.” Person Individual Differ 94 (2016): 38-43.

- Sbarra, David A, Hillary L Smith and Matthias R Mehl. “When Leaving your ex, Love Yourself: Observational Ratings of Self-Compassion Predict the Course of Emotional Recovery Following Marital Separation.” Psychol Sci 23 (2012): 261-269.

- Sewall, Craig Jeffrey Robb, Tina R Goldstein, Rachel H Salk and John Merranko et al. “Interpersonal Relationships and Suicidal Ideation in Youth with Bipolar Disorder.” Arch Suicide Res 24 (2020): 236-250.

- Simon, Robin W and Anne E Barrett. “Nonmarital Romantic Relationships and Mental Health in Early Adulthood: Does the Association Differ for Women and Men?.” J Health Soc Behav 51 (2010): 168-182.

- Slotter, Erica B, Wendi L Gardner and Eli J Finkel. “Who am I Without You? The Influence of Romantic Breakup on the Self-Concept.” Pers Soc Psychol Bull 36 (2010): 147-160.

- Till, Benedikt, Ulrich S Tran and Thomas Niederkrotenthaler. “Relationship Satisfaction and Risk Factors for Suicide.” Crisis 38 (2016) 7-16.

- Smyth, Kristin, Alison Salloum and Jaclyn Herring. “Interpersonal Functioning, Support, and Change in Early-Onset Bipolar Disorder: A Transcendental Phenomenological Study of Emerging Adults.” J Ment Health 30 (2021): 121-128.

- Verhallen, Anne M, Remco J Renken, Jan-Bernard C Marsman and Gert J Ter Horst. “Romantic Relationship Breakup: An Experimental Model to Study Effects of Stress on Depression (-like) Symptoms.” PLoS One 14 (2019): e0217320.

- Yarnell, Lisa M and Kristin D. Neff. “Self-Compassion, Interpersonal Conflict Resolutions, and Well-Being.” Self Identity 12 (2013): 146-159.

Citation: Rezapour, Roya, Shahram Vaziri and Farah Lotfi Kashani. “The Role of Romantic Breakup in Increasing Vulnerability to Emotional Disorders: A Systematic Review.” Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 15(2021). Doi: 10.3371/CSRP.RRSV.091521.

Copyright: © 2021 Rezapour R, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.