Research Article - Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses ( 2022) Volume 0, Issue 0

Problematic Internet Use and Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) Association among Adult Patients with Anxiety Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: An Exploratory Research

Mostafa O. Shahin, Yomna Alaa Mecdad, Dina Y. Afifi and Doaa R. Ayoub*Doaa R. Ayoub, Department of Psychiatry, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt, Email: drdoaariad@kasralainy.edu.eg

Received: 23-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. CSRP-22-72745; Editor assigned: 26-Aug-2022, Pre QC No. CSRP-22-72745 (PQ); Reviewed: 12-Sep-2022, QC No. CSRP-22-72745; Revised: 19-Sep-2022, Manuscript No. CSRP-22-72745 (R); Published: 27-Sep-2022, DOI: 10.3371/CSRP.SMYM.092722

Abstract

Background: Problematic internet use, internet addiction, and Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) levels are tremendously rising at the moment, while abundant studies reported the high prevalence of Internet Addiction among adolescents; only a few studies investigated their prevalence among adults with anxiety disorders and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. The objective of this exploratory research was to evaluate the levels of internet addiction and FoMO among patients with anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder and to investigate the association between internet addiction and FoMO in both disorders.

Methods: Forty patients with anxiety disorders and, OCD and 40 matched controls were assessed by Internet Addiction Test (IAT), FoMO scale, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A), and Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS).

Results: Internet addiction test mean scores were rather comparable between groups with no statistically significant difference (p=0.793). FoMO mean scores were significantly higher in the anxiety disorders group (p=0.017). There was a positive significant correlation between IAT and FoMO in both anxiety disorders and OCD subgroups (p=0.0001, p=0.037) respectively. Internet addiction and FoMO showed a significant positive correlation in both subgroups which were also more significant in anxiety disorders (p=0.0001).

Conclusion: Unexpectedly Internet Addiction showed rather similar levels between groups. FoMO severity was high, particularly in anxiety disorders. Additionally, Internet addiction and FoMO were positively correlated in anxiety disorders and OCD.

Keywords

Internet addiction • FoMO • Anxiety disorders • Obsessive-compulsive disorder • Early internet exposure

INTRODUCTION

Internet Addiction (IA) can be defined as a lack of control in the use of the Internet, in such a way that it impacts the personal life of the user [1]. Yet the term Internet addiction” has been criticized for being too unspecific in terms of content. Consequently, some scholars have suggested contentrelated addiction subtypes such as cybersexual addiction, social media addiction etc. [2].

Internet addiction is manifested in compulsive use of social networks, online shopping, games, etc, and a maladaptive usage of the net. This problem is difficult to address and has a risk of relapse, It is characterized by the appearance of withdrawal syndrome, a negative impact on the family environment, and an increasing desire of having more advanced software [3,4].

Over and above internet Addiction produces countless negative effects on the users' psychological well-being, this was manifested overtly during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns, the reporting rate of IA in young adults was found to be 28.1% [5].

Additionally, a substantial amount of research studies indicates that IA is strongly linked with an increased risk of self-harm. Moreover, an online survey held by Ozinci et al. revealed that individuals with IA had high rates of mental illness morbidity (65%), suicide ideation (47%), a lifetime of suicide attempts (23.1%), and suicide attempts in a year (5.1%) [6].

Internet addiction and problematic internet use were severe among patients with anxiety disorders. Socially anxious people are characterized by their immense fear of negative evaluation. Therefore, in social anxiety, virtual communication may become more appealing than face-to-face interaction. In a prospective study in Taiwan, the incidence of social phobia was found to predict the occurrence of internet addiction [7].

A high prevalence of IA in young individuals was reported in multiple studies [8,9], the younger generation in this modern era uses the computer at school or work more often compared to the older generations, which is linked to the high prevalence of IA in the younger age group. A recent systematic review showed that there is an increase in IA in the new generations, with other variables playing a relevant role, such as an increase in individualism, lower sociability, and enculturation [9].

Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) refers to individuals’ apprehension or concerns about missing or being absent or disconnected from an experience that others (i.e., peers, friends, family) might receive or enjoy and is highlighted as a key driver of the younger generation’s social media use [10].

FoMO is not a minor problem. Research suggests that FoMO, combined with the wide array of readily available communication technologies, may distract individuals from real extemporaneous social experiences in the physical world [11].

A study by Gupta and Sharma, investigated motivational, emotional, and behavioral correlates of fear of missing out and has shown that FoMO was negatively associated with both general mood and overall life satisfaction [12]. Another recent study concluded that there is a positive correlation between IA and FoMO. In other words, as the fear of missing the developments on social media increases, the risk of being an internet addict increases [13].

It is worth noting that despite the growing number of studies on IA, there is not yet an agreement on the conceptualization of Internetrelated problematic behaviors. IA has not been officially recognized as an independent psychiatric disorder by the APA. Of note, only Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD), one of the sub-types of IA, has been included in DSM-5. However, it was observed that more studies are needed, both in the context of IGD and IA, to update the proposed criteria [14]. One of the main reasons for this is the finding that patients with IA frequently have “comorbidities” with other psychopathological conditions, which may explain IA. Nonetheless, as it has this tremendous negative impact on mental health, whether it is a manifestation or an extension of the behavior resulting from underlying psychopathology, it is crucially important that patients presenting with IA as the principal complaint be screened for psychopathological and psychiatric conditions and vice versa [14].

This exploratory research hypothesized that patient with anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder, have higher levels of internet addiction and Fear of Missing Out than the healthy control group and that Internet addiction is positively correlated with Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) in both disorders. The objective of this research was to evaluate the levels of internet addiction and FoMO among patients with anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder and to investigate the association between internet addiction and FoMO in both disorders.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study is a case-control cross-sectional study. The sample included was a convenient one.

Sample size: The required sample size was forty for each group. Sample size calculation was done using (G*Power software version 3.1.9.2). The effect size was estimated from a previous study to be 1.06, α= 0.05, and power= 0.95.

Study site: Participants were recruited from both the inpatient unit and outpatient clinic of Psychiatry and Addiction Prevention Hospital, Kasr Al- Ainy Hospitals, Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was taken from each participant after explaining to them the aim and the details of this study. It was emphasized to the participants that participation in this study is voluntary and that it does not imply a direct benefit or harm for the participant. They were also informed that they were free to leave this study at any time without giving any justification nor will the latter affect the medical service provided in case of patients. In addition, participants were informed that the results of this study could be used as a scientific publication, but their identity will be confidential. The proposal was approved by the Scientific and Ethical Committee of the Department of Psychiatry of Kasr Al-Ainy. Then the Ethical Committee of Cairo University approved this research in January 2022 (Registration number: MS-548-2021).

Study participants: Eighty subjects aged 20 to 45 fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the study. They were divided into 2 groups.

First group: Forty patients with an anxiety disorder (General Anxiety Disorder, Social Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Specific Phobia) or obsessive-compulsive disorder) meeting the criteria in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition.

Inclusion criteria: Both sexes, Age: 20-45 years currently meeting DSM-5 criteria for an anxiety disorder or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Exclusion criteria: Refusing to sign the written consent, Illiterate, Having an intellectual disability, or having no internet access.

Second group (control group): Forty healthy individuals with no history of psychiatric disorders were matched with the patients’ groups for age, sex, education, and socio-demographic data. They were recruited from medical and paramedical employees in Kasr Al-Ainy Teaching hospitals. The two groups were matched for age, sex, education, and socio-demographic data.

Statistical analysis

The data was treated on a compatible personal computer using the statistical package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS-version 22) [15].

Procedure: The subjects were interviewed using Kasr Alaini semistructured psychiatric interview. and diagnoses were established according to the DSM-5 criteria [14].

For the anxiety disorders subgroup (HAM-A, IAT, FoMO).

For the OCD subgroup (YBOC-S, IAT, FoMO).

The Control group was assessed by GHQ-28 by Goldberg and Williams [16] in its Arabic version [17] to exclude any psychiatric morbidity. After excluding psychiatric morbidity in the control group, the following scales were applied (IAT, FoMO).

The Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) by Hamilton [18]. The scale consists of 14 items designed to assess the severity of a patient's anxiety. A validated Arabic version was used [19]. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) by Goodman et al. is a test to rate the severity of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) symptoms [20]. For Group A and B (Patient and control groups) the following tools were applied. The Internet Addiction Test by Young et al. to assess symptoms of Internet addiction and compulsivity in a variety of test settings [21]. A validated Arabic version was used [22]. The FoMO scale was developed by Przybylski et al. to assess the levels of FoMO [10]. A validated Arabic version of FoMO was used [23]. The time required to finish the assessment for each patient ranged around 1.5 hours and for each healthy control for around 1 hour.

Results

As shown in Table 1, in the anxiety disorders subgroup, 10% were males, and 90% were females. In the OCD subgroup, 35% were males and 65% were females. In the healthy control group, 37.5% were males, and 62.5% were females. There was no statistically significant difference between the three groups regarding gender (p=0.077). The age of the sample chosen was between 20-45 years. The mean age of the anxiety disorders subgroup was (25.6 ± 4.4), in the OCD subgroup (25.8 ± 3.9) and the healthy control (26.4 ± 2.7), There was no statistically significant difference between the patient’s group and the healthy control group regarding age as well (p=0.07). As for the marital status, as illustrated in Table 1, in the healthy control group, 82.5% (N=33) were single, and 17.5% (N=7) were married. In the anxiety subgroup, 75% (N=15) were single, 20% (N=4) were married and 5% (N=1) were divorced. In the OCD subgroup, 80% (N=16) were single and 20% (N=4) were married. There was no statistically significant difference between the three groups regarding marital status (p=0.531). All participants in the study were employed and educated. However, there was a statistically significant difference between the patient and the control group regarding employment (p=0.024) as well as education (p=0.017) as participants in the healthy control group were more employed and educated than the patients group.

| Healthy Control | Anxiety | OCD | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), M ± SD | 26.40 ± 2.71 | 25.60 ± 4.49 | 25.80 ± 3.98 | 0.668 | |

| Gender, N (%) | Male | 15 (37.5%) | 2 (10%) | 7 (35%) | 0.077 |

| Female | 25 (62.5%) | 18 (90%) | 13 (65%) | ||

| Marital Status, N (%) | Single | 33 (82.5%) | 15 (75%) | 16 (80%) | 0.531 |

| Married | 7 (17.5%) | 4 (20%) | 4 (20%) | ||

| Divorced | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Employment, N (%) | Unemployed | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10%) | 5 (25%) | 0.024 |

| Housewife | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Skilled | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (5%) | ||

| Professional | 23 (57.5%) | 8 (40%) | 8 (40%) | ||

| Student | 17 (42.5%) | 7 (35%) | 5 (25%) | ||

| Education, N (%) | Secondary School | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10%) | 0.017 |

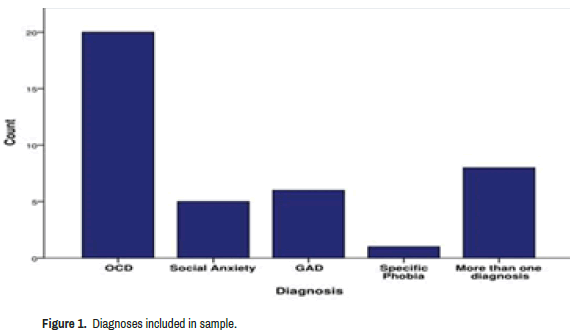

Figure 1 shows that 50% of the patient’s group were diagnosed with OCD (N=20), 15% (N=5) were diagnosed with Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) (N=6), 12.5% were diagnosed with social anxiety disorder (N=5), 2.5% were diagnosed with specific phobias (N=1). In the anxiety disorders subgroup, 20% of the patients (N=8) had another comorbid anxiety disorder.

As shown in Table 2, in the anxiety disorders subgroup, anxiety severity was higher in males compared to females with statistically significant differences p=0.028 respectively. While IAT and the FoMO Mean scores were higher in females but without statistically significant difference p=0.105, p=0.58.

| Sex | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age_1st_internet_use | Male | 2 | 14.0000 | 1.41421 | 0.183 |

| Female | 18 | 12.6667 | 1.28338 | ||

| IAT | Male | 2 | 36.0000 | 11.31371 | 0.105 |

| Female | 18 | 57.0000 | 16.74023 | ||

| FOMO | Male | 2 | 25.0000 | 4.24264 | 0.588 |

| Female | 18 | 28.3889 | 8.40965 | ||

| HAM_A | Male | 2 | 36.5000 | 0.70711 | 0.028 |

| Female | 18 | 30.5000 | 10.45579 | ||

Note: p<0.05 is significant; OCD: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, IAT: Internet Addiction Test, FoMO: Fear of Missing Out. |

|||||

As shown in Table 3, in the OCD subgroup, the IAT mean scores were 48.28 ± 16.38 in males and 55.5 ± 10.34 in females with no statistical difference (p=0.238). FoMO mean scores were 27.57 ± 11.9 in males and 25.3 ± 6.8 in females with no significant statistical difference (p=0.6).

| Sex | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age_1st_internet_use | Male | 7 | 13.0000 | 1.52753 | 0.302 |

| Female | 13 | 12.3077 | 1.31559 | ||

| IAT | Male | 7 | 48.2857 | 16.38815 | 0.238 |

| Female | 13 | 55.5385 | 10.34904 | ||

| FOMO | Male | 7 | 27.5714 | 11.98412 | 0.606 |

| Female | 13 | 25.3846 | 6.82567 | ||

| Female | 13 | 12.3846 | 4.94197 | ||

| YBOCS | Male | 7 | 16.7143 | 5.76525 | 0.073 |

Note: p<0.05 is significant; OCD: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, IAT: Internet Addiction Test, FoMO: Fear of Missing Out. |

|||||

In Table 4, the mean scores of the IAT were comparable among the 3 groups studied with no statistically significant difference. The mean scores of the FoMO scale in the anxiety disorders subgroup were 28 ± 8.08, the difference between the mean scores of the 3 groups was statistically significant (p=0.017). Fear of missing out was more severe in the anxiety disorders patients’ subgroup.

| N | Mean | Std. Deviation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IAT | Controls | 40 | 55.2 | 7.683 |

| Anxiety disorders | 20 | 54.9 | 17.298 | |

| OCD | 20 | 53 | 12.847 | |

| Total | 80 | 54.575 | 11.902 | |

| FoMO | Controls | 40 | 22.675 | 5.417 |

| Anxiety disorders | 20 | 28.05 | 8.081 | |

| OCD | 20 | 26.15 | 8.713 | |

| Total | 80 | 24.887 | 7.339 | |

Note: p<0.05 is significant; OCD: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, IAT: Internet Addiction Test, FoMO: Fear of Missing Out. |

||||

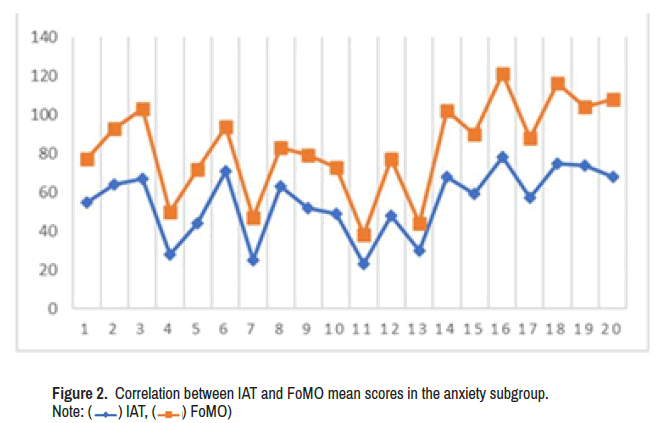

As illustrated in Table 5, a significant positive correlation, (r=0.73) was found between the mean scores of the IAT and FoMO scale (p=0.0001). There was a statistically significant positive correlation between age and 1st internet use (r=0.795, p=0.0001). HAM-A mean scores were positively correlated with IAT, and FoMO mean scores, however, the results were not statistically significant (p=0.997, p=0.574) respectively.

| Age | 1st internet use | IAT | FoMO | HAM_A | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | R | --- | 0.795 | -0.31 | -0.099 | 0.239 |

| P | 0 | 0.184 | 0.677 | 0.311 | ||

| Age of 1st internet use | R | 0.795 | ---- | -0.365 | -0.103 | -0.015 |

| P | 0.0001 | 0.113 | 0.665 | 0.949 | ||

| IAT | R | -0.31 | -0.365 | ---- | 0.734 | 0.001 |

| P | 0.184 | 0.113 | 0 | 0.997 | ||

| FoMO | R | -0.099 | -0.103 | 0.734 | ---- | 0.134 |

| P | 0.677 | 0.665 | 0.0001 | 0.575 | ||

| HAM_A | R | 0.239 | -0.015 | 0.001 | 0.134 | ---- |

| P | 0.311 | 0.949 | 0.997 | 0.575 | ||

Note: p<0.05 is significant; OCD: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, IAT: Internet Addiction Test, FoMO: Fear of Missing Out, HAMA: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; A Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the relationship between different variables. |

||||||

As illustrated in Figure 2, a significant positive correlation, (r=0.73) was found between the mean scores of IAT and FoMO scale (p=0.0001).

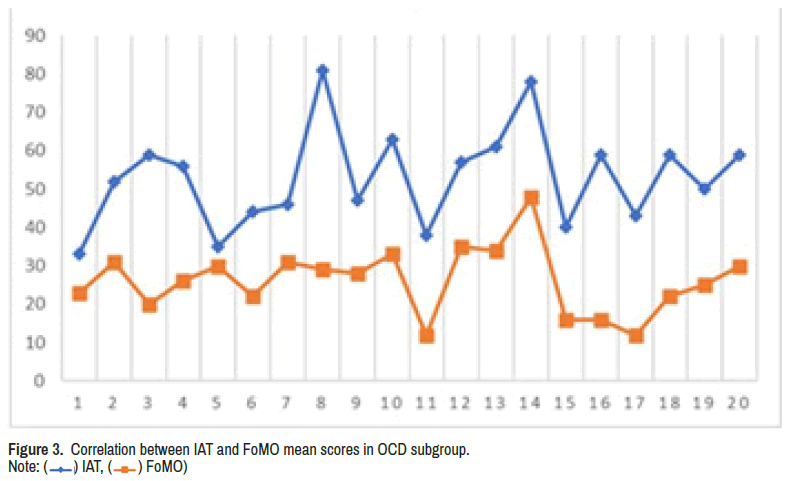

As illustrated in Table 6, a significant positive correlation, was found between the mean scores of the IAT and FoMO scale (r=0.47, p=0.0037). There was a statistically significant positive correlation between age and 1st internet use (r=0.76, p=0.0001).

| Age | 1st internet use | IAT | FoMO | YBOCS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | R | ---- | 0.762 | -0.289 | -0.177 | -0.242 |

| P | 0 | 0.217 | 0.455 | 0.303 | ||

| Age of 1st internet use | R | 0.762 | ----- | -0.34 | -0.237 | -0.189 |

| P | 0.0001 | 0.143 | 0.314 | 0.426 | ||

| IAT | R | -0.289 | -0.34 | ----- | 0.47 | 0.32 |

| P | 0.217 | 0.143 | 0.037 | 0.169 | ||

| FoMO | R | -0.177 | -0.237 | 0.47 | ----- | 0.104 |

| P | 0.455 | 0.314 | 0.037 | 0.662 | ||

| YBOCS | R | -0.242 | -0.189 | 0.32 | 0.104 | ----- |

| P | 0.303 | 0.426 | 0.169 | 0.662 | ||

Note: p<0.05 is significant; OCD: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, IAT: Internet Addiction Test, FoMO: Fear of Missing Out, HAMA: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; A Pearson correlation coefficient was computed to assess the relationship between different variables. |

||||||

As illustrated in Figure 3, a significant positive correlation was found between the mean scores of IAT and FoMO scale (r=0.47, p=0.0037).

Discussion

The current study aimed at assessing the levels of Internet Addiction (IA) and Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) amongst patients with anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder and to investigate the association between IA and FoMO in both disorders.

Discussion of descriptive data of the study sample

The age of the sample chosen was between 20-45 years. The mean age of the anxiety disorders subgroup was (25.6 ± 4.4), in the OCD subgroup (25.8 ± 3.9) and the healthy control (26.4 ± 2.7), and there was no statistically significant difference between the mean ages of the 2 groups, in related studies on internet addiction the age ranged from 16 years to a mean age of 30.5 years [24,25]. As for gender, in the healthy control group 37.5% (N=15) were males and 62.5% (N=25) were females, in the anxiety disorders subgroup 10% (N=2) were males, 90% (N=18) were females and finally, in the OCD subgroup 30% (N=7) were males and 65% (N=13) were females. Both groups were matched regarding gender (ρ=0.07), so neither age nor gender differences acted as a confounding factor in our study.

In the study at hand, all participants were educated yet all participants were not employed. There was a significant statistical difference in the number of formal years of education between the 2 groups and the employment (p=0.017), (p=0.024) respectively. There was a higher percentage of unemployment in the patient group 35% than in the healthy control group where none of them was unemployed. In the anxiety disorders subgroup, 40% (N=8) had a professional job, 35% (N=7) were students, 10% (N=2) were unemployed, 10% (N=2) had a skilled job and one female was a housewife In the Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) subgroup, 40% (N=8) had a professional job, 25% (N=5) were students, 25% (N=5) were unemployed, one female was a housewife 5%, 5%, and one patient had a skilled job.

The higher percentage of unemployment among the OCD subgroup reflects the relatively high level of functional impairment associated with OCD. The results are consistent with a study conducted Rodriguez-Salgado and colleagues which showed that OCD patients have higher unemployment rates, lower average income, and worse academic achievements as many patients are troubled by their symptoms which can affect their productivity [26].

Discussion of comparative data between anxiety disorders and OCD patients (regarding healthy controls)

So, by comparing both genders, IAT mean scores were higher in females (Males: 36 ± 11.31, Females: 57 ± 16.74) yet the results were statistically insignificant (p=0.105). However, the literature suggests that males were more likely to have IA compared to females [27,28]. The results in this study could be explained by the fact that IA was measured in this study without specifying which type of IA (e.g., gaming or social media addiction). Women were found to have more social media addiction than men who showed more addiction to gaming [29,30]. Another meta-analytic study by Su et al. in 2020 studied gaming addiction and social media addiction [31]. The meta-analysis comprised 53 effect sizes with 82,440 individuals from 21 countries for Internet gaming disorder, and 41 effect sizes with 58,336 individuals from 22 countries/regions for social media addiction. A randomeffects model confirmed important gender-specific differences as men were more likely to exhibit internet gaming disorder than women and less likely to exhibit social media addiction than women.

The level of IA was comparable between the groups examined. In the anxiety subgroup, the mean score was (54.9 ± 17.2) the mean score in the OCD subgroup (53 ± 12.8) and in the healthy control (55.2 ± 7.6) however, these results were found to be statistically insignificant (p=0.793). Similar to a previous study by de Vries et al. which aimed at studying the prevalence of IA and psychiatric co-morbidity among adult psychiatric patients showed that the prevalence of IA was higher in adult psychiatric patients (25%) than that of the general population (6%) [32]. In addition, IA in psychiatric patients was associated with higher scores on questionnaires investigating anxiety and OCD. Still, their results comparing anxiety disorders and OCD regarding the severity of IA were indistinguishable which is in line with our study.

It is rather acceptable to deduce that the more severe the psychiatric illness of the studied population, the higher the prevalence of internet addiction. Yet due to its cross-sectional nature, our study was unable to identify any causal relationship between Internet addiction and psychiatric disorders. Further study to reveal the causal relationship between psychiatric symptoms and IA is needed which will show the difference in IA between patients and healthy individuals.

In contrast, Lee et al. research revealed that the internet was used by anxious patients as a tool for interaction to avoid fears of negative evaluation, especially in social anxiety disorder, and as a means to reduce the level of discomfort by virtually interacting with others [33].

Fear of Missing Out refers to the anxiety a person experiences when they feel that they are missing out on information, events, experiences, or life decisions that could make one's life better.

FoMO test mean scores were higher in females (25 ± 4.24) than males (28.3 ± 8.4), but the results were also statistically insignificant (p=0.588). Previous studies have demonstrated that FoMO was higher in females [34,35].

On the other hand, a study by Rozgonjuk et al. in 2021 assessed gender differences regarding experiencing FoMO, by using the FoMO scale, and they found no gender differences regarding experiencing FoMO [36].

Levels of FoMO in the anxiety disorders subgroup were highest (28 ± 8.08), followed by the OCD subgroup scores (26.15 ± 8.71), and lowest in the healthy control group (22.67 ± 5.42) with a statistical difference of (p=0.02). People with social anxiety worry about missing out on rewarding experiences and are more likely to excessively use their smartphones to alleviate their FoMO. Related work recently demonstrated that FoMO severity was positively correlated with the severity of social anxiety [37,38].

Discussion of the correlative data between the anxiety disorders and OCD subgroups

There was a statistically significant positive correlation between younger age and age of 1st internet use in the anxiety and OCD subgroups (p=0.0001). This means that patients with anxiety disorders use the internet at an earlier age. There is no robust evidence in the literature on whether patients with anxiety disorders use the internet at a younger age than healthy individuals. However, these results are consistent with reports indicating older children and young adults were introduced to the internet at a younger age, thus came the term (Digital natives) [39].

Correlation between mean scores of IA and FoMO in both subgroups

As for the association between IA and FoMO, there was a significant statistically positive correlation between both. In the OCD subgroup, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between IA and FoMO (p=0.037). The statistical significance was higher in the anxiety disorder subgroup with a statistical significance (p=0.0001). These findings are consistent with prior research on the FoMO-IA relationship [40, 41] as social media indeed plays a fundamental role in the fear of missing out. Furthermore, it is reasonable to assume that the higher the severity of psychiatric illness of the studied population, the higher the prevalence of IA. Yet most likely due to its cross-sectional nature, this study was unable to identify any causal relationships between IA and psychiatric disorders. Our findings nonetheless may encourage future longitudinal studies aimed at identifying the potential causal relationship between different psychiatric symptoms and IA.

Conclusion

Unexpectedly this research revealed that internet addiction was comparable across patients and healthy individuals. However, the severity of FoMO was shown to be high, particularly in anxiety disorders. Additionally, another outcome was that IA and FoMO were positively correlated in both anxiety disorders and OCD.

Strengths

To the knowledge of the researchers, this study was the first to investigate the levels of IA and FoMO amongst patients with anxiety disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder and to investigate the association between IA and FoMO in both disorders. This research investigated IA and FoMO in an older population than most similar studies in which adolescents were tested. This study found a positive link between the age of first internet use and anxiety disorders a patient which is a disturbing finding that merits further studying and exploration on larger samples.

Limitations

Nevertheless, there were some limitations in our research first, the relatively small sample size, the small sample size does not allow precise estimates, and larger confirmatory studies are needed. Moreover, the sample of the present study was a convenience sample of adults with anxiety disorders and OCD. Future studies with random sampling methods on other wider age ranges and cultural contexts are needed. Secondly, all patients were sampled from Kasr Al-Ainy hospital, which is a governmental hospital so, there was some difficulty in finding patients who have internet access because of the awfully low socioeconomic level. Despite these limitations, this study provides new insight into the IA and FoMO among patients with anxiety disorders and OCD which merits further studying.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to all the patients who participated in the study, for their valuable cooperation and generous time without whom the study could not have been accomplished.

Authors’ Contributions Statement

Study conception and design: SM, AD, YD and AY. Data collection: AY. AY, AD, YD Data analysis and interpretation: AD Drafting of the main manuscript. SM, and AD. AY: prepared figures and tables. Critical revision of the article: SM, AD, YD, and AY read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

It was all covered by the research team. The study received no funding grants.

Availability of Data and Materials

Available data and material upon request.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of the Psychiatry Department and the Faculty of Medicine, Cairo University, Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. The objectives and aims of the study were clarified to the participants. The subjects were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time yet this didn't affects the service offered to them.

Consent for Publication

Oral consent from the study subjects was obtained for publication.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

References

- Poon, Kai-Tak. "Unpacking the Mechanisms Underlying the Relation between Ostracism and Internet Addiction." Psychiatry Res 270 (2018): 724-730.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Young, Kimberly. "The Evolution of Internet Addiction Disorder." Internet addiction (2017): 3-18.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Lindenberg, Katajun, Carolin Szasz-Janocha, Sophie Schoenmaekers and Ulrich Wehrmann, et al. "An Analysis of Integrated Health Care for Internet Use Disorders in Adolescents and Adults." J Behav Addict 6 (2017): 579-592.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Müller, Silke M., Elisa Wegmann, Dario Stolze and Matthias Brand. "Maximizing Social Outcomes? Social Zapping and Fear of Missing Out Mediate the Effects of Maximization and Procrastination on Problematic Social Networks Use." Computers in Human Behavior 107 (2020): 106296.

- Liang, Leilei, Chuanen Li, Cuicui Meng and Xinmeng Guo, et al. "Psychological Distress and Internet Addiction Following the COVID-19 Outbreak: Fear of Missing out and Boredom Proneness as Mediators." Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 40 (2022): 8-14.

- Ozinci, Zeynep, Juvaria Anjum, Rashi Aggarwal. "Internet Addiction and Self-Harm/Suicide: How Are They Related?" In 65th Annual Meeting. AACAP. 2018.

- Ko, Chih-Hung, Ju-Yu Yen, Cheng-Sheng Chen and Yi-Chun Yeh, et al. "Predictive Values of Psychiatric SYmptoms for Internet Addiction in Adolescents: A 2-year Prospective Study." Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 163 (2009): 937-943.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Kim, Byung-Soo, Sung Man Chang, Jee Eun Park and Su Jeong Seong, et al. "Prevalence, Correlates, Psychiatric Comorbidities, and Suicidality in a Community Population with Problematic Internet Use." Psychiatry Res 244 (2016): 249-256.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Lozano-Blasco, Raquel, Alberto Quilez Robres, Alberto Soto Sánchez. "Internet Addiction in Young Adults: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review." Computers in Human Behavior (2022): 107201.

- Przybylski, Andrew K., Kou Murayama, Cody R. DeHaan and Valerie Gladwell. "Motivational, Emotional, and Behavioral Correlates of Fear of Missing Out." Computers in human behavior 29 (2013): 1841-1848.

- Turkle, Sherry. “Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other”. 2017.

- Gupta, Mayank, Aditya Sharma. "Fear of Missing Out: A Brief Overview of Origin, Theoretical Underpinnings and Relationship with Mental Health." World J Clin Cases 9 (2021): 4881-4889.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Kargın, Maral, Hilal Türkben Polat, Didem Coşkun Şimşek. "Evaluation of Internet Addiction and Fear of Missing out Among Nursing Students." Perspect Psychiatr Care 56 (2020): 726-731.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Edition, Fifth. "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders." Am Psychiatric Assoc 21(2013): 591-643.

- IBMCorp Ibm, SPSS. "Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0." Armonk, NY: IBM Corp (2017).

- Goldberg, David P., Valerie F. Hillier. "A Scaled Version of the General Health Questionnaire." Psychol Med 9 (1979): 139-145.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Alhamad, Abdulrazzak, Eiad A. Al-Faris. "The Validation of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28) in a Primary Care Setting in Saudi Arabia." J Family Community Med 5 (1998): 13.

[Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Hamilton, MAX. "The Assessment of Anxiety States by Rating." Br J Med Psychol (1959).

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Lotfy, F. "Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A)." Anglo Egyptian Library, Cairo, Egypt (1994).

- Goodman, Wayne K., Lawrence H. Price, Steven A. Rasmussen and Carolyn Mazure, et al. "The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: I. Development, Use, and Reliability." Arch Gen Psychiatry 46 (1989): 1006-1011.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Liebert, Mary Ann. "Internet Addiction: The Emergence of New Clinical Disorder." Cyber Psychology & Behavior 1 (1998): 1-9.

- Hawi, Nazir S. "Arabic Validation of the Internet Addiction Test." Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 16 (2013): 200-204.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Al-Menayes, Jamal. "The Fear Of Missing Out Scale: Validation Of The Arabic Version And Correlation With Social Media Addiction." Int J App Psychol 6 (2016): 41-46.

- King, Daniel L., Paul H. Delfabbro, Mark D. Griffiths and Michael Gradisar. "Cognitive‐Behavioral Approaches to Outpatient Treatment of Internet Addiction in Children and Adolescents." J Clin Psychol 68 (2012): 1185-1195.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Dufour, Magali, Louise Nadeau and Sylvie R. Gagnon. "Internet Addiction: A Descriptive Clinical Study of People Asking for Help in Rehabilitation Treatment Center in Quebec: Exploratory Study/Tableau Clinique des Personnes Cyberdependantes Demandant des Services dans les Centres Publics de Readaptation En dependance au Quebec: Etude Exploratoire." Sante ment Que 39(2014): 149-169.

[Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Rodriguez-Salgado, Beatriz, Helen Dolengevich-Segal, Manuel Arrojo-RomeroA and Paola Castelli-Candia, et al. "Perceived Quality of Life in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Related Factors." BMC psychiatry 6 (2006): 1-7.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Bakken, Inger Johanne, Hanne Gro Wenzel, K. Gunnar Götestam and Agneta Johansson, et al. "Internet Addiction Among Norwegian Adults: A Stratified Probability Sample Study." Scand J Psychol 50 (2009): 121-127.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Morrison, Catriona M. and Helen Gore. "The Relationship between Excessive Internet Use and Depression: A Questionnaire-Based Study of 1,319 Young People and Adults." Psychopathology 43 (2010): 121-126.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Schou Andreassen, Cecilie and Stale Pallesen. "Social Network Site Addiction-an Overview." Current Pharm Des 20 (2014): 4053-4061.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Andreassen, Cecilie Schou, Ståle Pallesen, Mark D. Griffiths. "The Relationship between Addictive Use of Social Media, Narcissism, and Self-Esteem: Findings from a Large National Survey." Addict Behav 64 (2017): 287-293.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Su, Wenliang, Xiaoli Han, Hanlu Yu and Yiling Wu. "Do Men Become Addicted to Internet Gaming and Women to Social Media? A Meta-Analysis Examining Gender-Related Differences in Specific Internet Addiction." Comp Hum Behav 113 (2020): 106480.

- de Vries, Hille T., Takashi Nakamae, Kenji Fukui and Damiaan Denys. "Problematic Internet Use and Psychiatric Co-Morbidity in a Population of Japanese Adult Psychiatric Patients." BMC Psychiatry 18 (2018): 1-10.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Lee, Bianca W. and Lexine A. Stapinski. "Seeking Safety on the Internet: Relationship between Social Anxiety and Problematic Internet Use." J Anxiety Disord 26 (2012): 197-205.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Beyens, Ine, Eline Frison and Steven Eggermont. "“I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing”: Adolescents’ Fear of Missing Out and its Relationship to Adolescents’ Social Needs, Facebook Use, and Facebook Related Stress." Comp Hum Behav 64 (2016): 1-8.

- Stead, Holly, and Peter A. Bibby. "Personality, Fear of Missing Out and Problematic Internet Use and Their Relationship to Subjective Well-Being." Comp Hum Behav 76 (2017): 534-540.

- Rozgonjuk, Dmitri, Cornelia Sindermann, Jon D. Elhai, and Christian Montag. "Individual Differences in Fear of Missing Out (FoMO): Age, Gender, and the Big Five Personality Trait Domains, Facets, and Items." Personality and Individual Differences 171 (2021): 110546.

- Oberst, Ursula, Elisa Wegmann, Benjamin Stodt and Matthias Brand, et al. "Negative Consequences from Heavy Social Networking in Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Fear of Missing out." J Adolesc 55 (2017): 51-60.

- Wolniewicz, Claire A., Mojisola F. Tiamiyu, Justin W. Weeks and Jon D. Elhai. "Problematic Smartphone Use and Relations With Negative Affect, Fear of Missing Out, and Fear of Negative and Positive Evaluation." Psychiatry Res 262 (2018): 618-623.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Dingli, Alexiei and Dylan Seychell. "The New Digital Natives." Cutting the Chord (2015).

- Błachnio, Agata, and Aneta Przepiórka. "Facebook Intrusion, Fear of Missing Out, Narcissism, and Life Satisfaction: A Cross-Sectional Study." Psychiatry Res 259 (2018): 514-519.

[Crossref] [Google scholar] [Pubmed]

- Dhir, Amandeep, Yossiri Yossatorn, Puneet Kaur and Sufen Chen. "Online Social Media Fatigue and Psychological Wellbeing—A Study of Compulsive Use, Fear of Missing Out, Fatigue, Anxiety and Depression." Int J Inf Manag 40 (2018): 141-152.

Citation: Shahin, Mostafa O, Yomna Alaa Mecdad, Dina Y. Afifi and Doaa R. Ayoub. “Problematic Internet Use and FoMO Association among Adult Patients with Anxiety Disorders and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: An Exploratory Research.” Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 16S (2022). Doi: 10.3371/CSRP.SMYM.092722.

Copyright: © 2022 Shahin MO et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

) IAT, (

) IAT, ( ) FoMO

) FoMO