Research Article - Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses ( 2023) Volume 17, Issue 5

Fluctuating Adaptation in Caregivers of Schizophrenia Patients: The Process of Caregiver Preparedness in Their Families-A Grounded Theory Study

Azadeh Eghbal Manesh1*, Mohammad Zoladl2 and Asghar Dalvandi12Department of Nursing, Yasuj University of Medical Sciences, Yasuj, Iran

Azadeh Eghbal Manesh, Department of Nursing, Tehran Medical Science, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran, Tel: 989178082104, Email: azal_ta_abad2020@yahoo.com

Received: 24-Mar-2023, Manuscript No. CSRP-23-92711; Editor assigned: 27-Mar-2023, Pre QC No. CSRP-23-92711 (PQ); Reviewed: 11-Apr-2023, QC No. CSRP-23-92711; Revised: 12-Jun-2023, Manuscript No. CSRP-23-92711 (R); Published: 19-Jun-2023

Abstract

Introduction: Schizophrenia is a chronic life-devastating disease with bizarre symptoms managed by family caregivers. As one of the most important components of caring is caregiving preparedness, this study aims to explore this process in families of schizophrenia patients in Iran.

Methods: After explaining our goals and obtaining written consent, we conducted twenty semi-structured interviews with family members and healthcare providers of schizophrenia patients. Then recorded their voices, transcribed them verbatim, analyzed them, and estimated their trustworthiness each session.

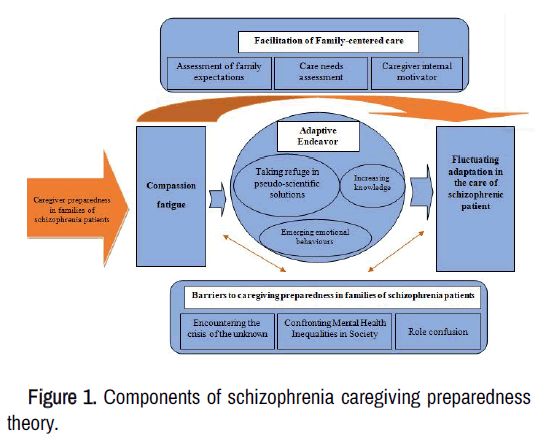

Result: This theory is made up of six main themes, including "encountering the crisis of the unknown," "confronting mental health inequalities in society," "role confusion," "facilitating family-centred care," "adaptive endeavor," and "fluctuating adaptation in the care of schizophrenia patients."

Conclusion: The findings of this study highlighted barriers, facilitators, strategies, and consequences of the caregiving preparedness process. These findings can be used in evidence-based care, better-educating caregivers and guiding a better understanding of this issue for health policymakers.

Keywords

Caregiving preparedness • Readiness • Schizophrenia patients • Family caregivers • Qualitative study

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe psychological disease that can cause delusions, hallucinations, and very messed-up thinking, making it hard to function and requiring treatment for the rest of one's life [1]. Schizophrenia makes people weak, so it is one of the top twenty leading causes of disability worldwide [2]. Also, it may impact daily activities, such as work and relationships with family and friends, as well as social interaction and productivity [3].

Deinstitutionalization and the transition to community mental health care resulted in a gradual decrease in the number of hospital beds for the mentally ill, imposing a significant responsibility for consideration on the families of those with mental illness. According to the World Health Organization, between 40 and 90 percent of schizophrenia patients live with their families [4]. Due to statistically considerable deficits, schizophrenia patients rely on caregivers.

Families are supposed to provide most of the care; they spend a lot of time caring for mentally ill family members while fearing recurrence and worrying about the disease's influence on other family members [5]. Worldwide, there are issues and pressures that caregivers of people with mental illnesses must deal with, including stigma and inadequate stress management approaches [6].

Some family caregivers lack the necessary skills to perform their roles. Caregiving involves a lot of different tasks that all have to do with each other. These tasks include coordinating inhome community services, giving emotional support, dealing with the stress of caregiving, and giving physical care [7]. Caregiver preparedness refers to being ready for various aspects of one's role as a caregiver [8]. Increasing caregiver preparedness can help family members choose effective ways to deal with the symptoms, understand recovery and its process, strengthen communication skills, and prevent relapse. It can also support them through prevention strategies such as knowing early warning signs, stress management training, and methods to help in times of crisis [9]. Understanding this process is essential because a lack of knowledge, inadequate perception of the caregiving role, and caregiver feeling of inadequacy can make the symptoms return shortly after discharge [10]. This issue can lead to frequent hospitalizations and high financial costs for individuals and the healthcare system. These problems continue for the family and society as a vicious cycle [11].

On the other hand, caring for a person with a mental illness differs from caring for physical problems [12]. However, most previous studies in this field have been done on people with physical issues such as cancer, Alzheimer's, stroke, disabled, and need for palliative care [13-18]. To the best of our knowledge, no qualitative studies are exploring the process of caregiving preparedness in families of schizophrenia patients. Analyzing this process can help identify traits, preconceptions, facilitators, barriers, and the structure of caregiver preparedness in psychiatric centers. Also, these findings can be used in evidence-based care, better-educating caregivers, and guide a better understanding of this issue for health policymakers. Consequently, our grounded theory study was conducted with the purpose of exploring the process of caregiving preparedness in family caregivers of schizophrenia patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The present study is a qualitative work with a grounded theory design, as recommended by Corbin and Strauss. The grounded theory is a method of thinking and studying social phenomena that answers how individuals respond to events or handle problems through action and interaction [19]. Since caregiver preparedness is established via social interactions and individuals confront it in that setting, the grounded theory applies to the research.

Participants and research setting

The participants in this study were ten family caregivers of schizophrenia patients and four key informants, such as one psychiatric nurse, two psychiatrists, and one occupational therapist. The demographic characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1.

| Codes | Gender | Age | Educational level | Relationship between caregiver and patient | Duration of the interview | Duration of patient care | Number of patient admissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Male | 42 | Bachelor's degree | Brother | Two sessions (1 h) | 8 Years | Twice |

| P2 | Female | 23 | Bachelor's degree | Child | One session (35 min) | 10 Years | Twice |

| P3 | Female | 40 | Associate degree | Sister | Two sessions (1/5 h) | 5 Years | Twice |

| P4 | Female | 48 | Guidance | Sister | One session (50 min) | 12 Years | Third |

| P7 | Female | 54 | High school | Sister | Three sessions (1/5 h) | 6 Years | Twice |

| P8 | Female | 28 | Diploma | Husband | Two sessions (45 min) | 3 Years | Twice |

| P9 | Female | 47 | Diploma | Mother | Two sessions (2/15 h) | 14 Years | Twice |

| P10 | Female | 44 | Diploma | Sister | One session (30 min) | 7 Years | Seventh |

| P11 | Female | 24 | University student | Child | One session (1/5 h) | 8 Years | Twice |

| P12 | Female | 54 | Diploma | Mother | One session (1/5 h) | 18 Years | Fifth |

| P5 | Male | 41 | Psychiatrist | - | One session (40 min) | - | - |

| P6 | Female | 36 | Master of psychiatric nursing | One session (45 min) | - | - | |

| P13 | Male | 39 | Occupational Therapist | - | One session (35 min) | - | - |

| P14 | Female | 39 | Psychiatrist | - | One session (1 h) | - | - |

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the participants (n=14).

The inclusion criteria for family caregivers consisted of having cared for an individual with schizophrenia hospitalized at least twice, wanting to share experiences, and speaking Persian. The researcher used purposive and theoretical sampling to understand the concepts and their relationships. Theoretical sampling was conducted to select the following participants or ask exploratory questions in the same or other interviews. For example, when the fourth participant talked about the lack of empathy in healthcare providers, the researcher decided to interview the psychiatrist for verification by theoretical sampling. The study setting included psychiatric hospitals in Shiraz and on Instagram and WhatsApp, either in writing or by phone. Participants chose the time and place of the interview to feel more comfortable. Because of the situation in Corona and safety concerns, the researcher didn't do the interviews at home.

Data collection and analysis

In-depth interviews with the participants were conducted in 2021-2022, using field notes and semi-structured and unstructured interview questions. The interviews could have lasted between 30 and 60 minutes, depending on how willing the participants were. Twenty interviews were conducted for this study. The first round of interviews, which were unplanned, consisted of asking general questions. What comes to mind when you hear "schizophrenia patient care"? For instance, when asked about family caregivers. The results showed detailed, reliable, and transparent information about how family caregivers felt about being ready to provide care, which helped narrow the questions and clarify the ideas. The recorded data from the interviews were transcribed and formatted to allow the authors to revise. The codes were compared and classified by asking multiple questions. Similar codes were put into groups based on their importance, given proper names, and then turned into concepts. In the next step, analyzing the data for context, the researcher looked at a set of conditions and situations that affected the participants and led to the main concern, "compassion fatigue." After incorporating the procedure into the analysis, the strategies and results that family caregivers used to deal with the main concern were found. After combining all the categories, the core category was extracted [19].

The trustworthiness of the data and findings

The criteria for conformability, transferability, credibility, and reliability set out by Guba and Lincoln in 1986 were used to examine the data [20]. To do this, the researcher spent much time with eight caregivers and three healthcare providers and read the transcripts more than once to understand better what was being said. Initial codes for interviews were given back to the people who took part as a way to check for accuracy. Six other faculty members who are qualitative researchers and mental health nursing experts also did a peer review. In addition, it was attempted to select the participants with the maximum variances from different groups of participants.

Results

Most participants (11, 78.57%) were female and between 24 and 54 years old (mean age=39). In this study, family caregivers used "adaptive endeavor" to get ready for caregiving by "taking refuge in pseudo-scientific solutions," "increasing knowledge," and "emerging emotional behaviors" in response to "compassion fatigue," which was their main concern. The people who took part in the study said that the "adaptive endeavor" strategy was necessary because of things like family expectations, an assessment of care needs, and the internal motivations of caregivers. Getting ready is a lifelong process for a caregiver, so "adaptive endeavors" are a crucial strategy chosen by the families of people with schizophrenia. It can make caregivers feel like they have "hopeful mastery of the situation" and "weakened power." The results for each phase of the Corbin and Strauss method are reported below.

Open coding to identify concepts

After the initial interview, the open coding phase started. By reading the transcripts and separating and highlighting the text, we learned more about the interviews and what they were. As shown in Table 2, labels for some concepts were determined based on "in vivo coding" (to assign labels based on what participants said), whereas we used quotation interpretation for others.

Development of concepts based on their features and dimensions

This theory consists of six categories, sixteen subcategories, and fifty-eight concepts. Concepts are the labels assigned to the participants' statements at the first level. According to their similarities, concepts were grouped into subcategories. Subcategories were then combined to form categories. Table 2 demonstrates the formation and development process of the role confusion concept.

| Category | Subcategory | Main codes | Quotation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Role confusion

|

Experience of mourning in the caregiver’s role

|

Denying | “I could not accept that my first child had this disease, and I was in a stupor” (P12). |

| Feeling hopeless | “I was disappointed, for example that the neighbors said to inject him and let him die” (P4). | ||

| Feeling afraid | “Doctor, we are terrified that those initial symptoms will recur” (P3). | ||

| Uncertainty about the future | “Now I am seven months pregnant, but I will say again, what if my child gets this disease?” (P8). | ||

| Feeling exhausted | “I am worn out and bothered by Mom” (P11). | ||

| Delegation of authority | “Of course, it can also be to escape from their care... By escaping, a younger person may take care of their patients instead and feel more at ease” (P6). | ||

| Escape from the caregiving role | Looking for a sponsor | “We have been looking for a good maintenance center for a month now, and we have to go somewhere, or they give exorbitant prices with unknown handling looking for a sponsor” (P10). |

Table 2. An example of the formation of the conception of role confusion.

Main concerns (compassion fatigue)

One of the first steps in analyzing the data was to figure out what the main concerns of family caregivers of people with schizophrenia were. When care was moving from the hospital to the home, the families had to deal with an unknown crisis, inequalities in mental health in society, and role confusion. In this study, "compassion fatigue" was identified as the primary concern of family caregivers. This worry got worse when families didn't know enough about caregiving and didn't know what their roles were.

Analyze data for context

Using data analysis, the researchers tried to find out what had happened to the participants that made them act in a certain way. Here's a summary of what they found:

Encountering the crisis of the unknown: The first and most crucial step in caregiving is having enough information about the disease. In this study, facing the crisis of the unknown is one of the reasons why family caregivers of people with schizophrenia choose the "adaptive endeavor" strategy. This strategy is broken down into two subcategories: "lack of family awareness" and "insufficient information resources."

Lack of awareness of families: We all know that a lack of knowledge among family caregivers can lead to several problems, such as a lack of disease management, a decline in the patient's health, poor quality of life, an increase in the burden on family caregivers, and the use of unhealthy ways to deal with stress. The experiences of the family caregivers in this study revealed that they did not know enough about the disease, its causes, and how to treat it in general [34].

"Unfortunately, because I didn't know enough about this disease the first time, it went away for a while. But the next time, it got so bad that my patient had suicidal thoughts, so we forced her to go to the hospital" (P1).

Insufficient informational resources: Family caregivers of people with schizophrenia can get health information from websites, pamphlets or leaflets, books or videos that explain the patient's illness and treatment, and links to local community resources or support groups. In this study, many family caregivers talked about how hard it was to find information written in simple, easy-to-understand language. Most of them were upset that there needed to be a knowledgeable person with whom they could share their problems. As one of them indicated: "I was on many pages about schizophrenia." They all claim to be this or that; but unfortunately, they do not provide appropriate solutions (P7).

Confronting mental health inequalities in society: In addition to the previous category, this category is one of the crucial barriers to caregiving preparedness. Mental health inequality is when there are differences in the quality, access, and type of mental health services that different communities and populations get. It has four subcategories: "social pressure," "health and therapeutic challenges," "little attention of policymakers to the problems of mentally ill families," and "weakness in cultural reflection." This article says that social, economic, cultural, political, health, and medical factors are essential in creating caregiver readiness in families.

Social pressure: Social pressure is one of the oldest issues that psychiatric patients and their families struggle with. Participants in this study talked about being ignored by themselves, their patients, the community, and others. The participants' experiences showed that, in many cases, people still have low awareness of psychiatric illnesses and have a negative view of them, which has led to challenges for them, as one of the psychiatrists noted below:

"Next is the social and family stigma that families have." "They hide their patients and do not take them to the doctor until their conditions worsen" (P14).

Health and therapeutic challenges: Most family caregivers noted health and therapeutic challenges. They face a lack of social and educational support, rejection, a lack of psychiatric emergencies to transport patients to psychiatric hospitals, missed follow-up and psychological rehabilitation, and less money from the health community and services. As one of the caregivers stated:

"Unfortunately, he always resists going." Not even a social emergency cooperates. They will eventually take him by force unless we pay $300,000 to transport him by ambulance and 110. It is like a thief and a murderer. "It's so awful here" (P10).

Little attention from policymakers to the problems of mentally ill families: The family caregivers said that their patients could not work as a way to get better, that it was too expensive, that some drugs were not covered by insurance because of sanctions against Iran, and that there was not enough money for their treatment. As a psychiatric nurse said: “I remember we wanted to discharge my mother; her hospital cost was about five and a half million tomans, but they didn't keep her for more than 50 days and accounted for her without insurance” (P11).

Weaknesses in cultural reflection: The participants' experiences showed that the community still thought of psychiatric disorders as taboo and all psychiatric patients as crazy. On the other hand, this leads to shame and feelings of embarrassment and secrecy in caregivers. The media have made this problem worse for patients and their families in the following ways:

"The media rarely covers the issues of the mentally ill." "If they make a film about patients, they will show them as crazy and highlight their disabilities" (P2).

Role confusion: One thing that makes it hard for families to get ready to care for someone with schizophrenia is that caregivers don't know their roles. This state may last until the end of care for the patient. This is one of the most important things to think about in the context of caregiving. Role confusion starts with grief, denial, hopelessness, fear, not knowing what the future will bring, and tiredness. This process may continue for the caregiver, who may want to give his job to someone else as a sponsor or get away from his caring career because he is too tired. One of the caregivers talks about this issue like this:

Experience of mourning in the caregiver's role: People with schizophrenia often go through the worst parts of their youth and adolescence when they are sick, which is a significant loss for their families. Participants in this study experienced different emotions in mourning [38].

"Poor my father; I cannot listen to his words even for one day." "I am upset as if I have been caught and hit on the wall" (P7).

Escape from the caregiving role: Caring for a schizophrenic patient with a chronic disease is a stressful situation that usually falls on the shoulders of one of the caregivers, and the others ignore it. For this reason, the participants' experiences in this research have indicated that after a period of caregiving, families feel burned out in their roles, and some choose to get rid of them. As one of the psychiatrists stated:

"I have talked to families many times; it is not out of pity; it is not because now they are waiting to see their grandson." For instance, when the parents are upset, they might say, "Well, if he gets married, then someone else will take care of him." (P5).

Facilitation of fdcentre-amily care: This category showed factors that facilitated caregiver preparedness. Centered family care is an innovative approach for planning, implementing, and evaluating care based on mutual collaboration between patients, families, and healthcare providers. It is based on the participation of patients and their families in care decisions. It includes three subcategories: “assessment of family expectations,” “care needs assessment,” and “caregiver internal motivator,” which come below:

Assessment of family expectations: In the present research, the patients' families had expectations at the time of discharge from the hospital, most of which still needed to be met by the healthcare providers. Most people who took part said they should have known more about how medications work, their side effects, how to control diseases, and how to treat patients. They still need to receive this training upon discharge.

"I expected at least they would tell me these things there "(P9).

Care needs assessment: Even though figuring out care needs is one of the essential parts of care, healthcare providers sometimes don't do it. As the following story shows, this makes it hard for caregivers to be ready after the patient is discharged.

"They (healthcare providers) could even give us at least a pamphlet; a pamphlet is a minimum, and they can ask how literate they are" (P3).

Caregiver internal motivator: This study found that the caregivers have strong willpower and empathy, get help from those around them, and work well with others. This means they are more ready to provide care. Also, the sense of motherhood is very influential in this process.

"One is that willpower helped me; the other is the sense of motherhood." I was a mother, tireless, and did not give up. "I could not accept that Saeed, my first child, would get this disease and take medicine, and until the end of his life, he lay on the bed like a corpse" (P12).

Bringing the process into data analysis

The process is the flow of actions, interactions, and emotions in response to events and problems. In the end, these processes lead to outcomes and consequences. People give answers rooted in situations, issues, circumstances, and events. After figuring out the problem, the researcher tried to find out how the participants felt and what they did to deal with their concerns. Applying these strategies can have different consequences in the caregivers' lives. In all the steps in the process of caregiving preparedness, the family caregivers tried to cope with their caring roles, so we selected the concept of "adaptive endeavor" as a core category.

Adaptive endeavor: Since schizophrenia affects every part of a caregiver's life, they try to change their roles in different ways, like "taking refuge in pseudo-scientific solutions," "increasing knowledge," and "emerging emotional behaviors." Families used these strategies in response to their primary concern of "compassion fatigue." "Adaptive endeavor" is the core category in preparing a caregiver. It has three subcategories: "taking refuge in pseudo-science solutions," "increasing knowledge," and "emerging emotional behaviors."

Taking refuge in pseudo-scientific solutions: In Iranian culture, several people still attribute psychiatric diseases to exorcism, sore eyes, magic, charm, etc. Family members of patients often stray from the right treatment path because they get the wrong advice from others and turn to pseudo-scientific methods to help their loved ones [43]. The other reasons are a lack of awareness and the absence of well-informed people to guide them correctly, which disappoints them in the treatment. Caregivers turned to fortunetelling, energy therapy, and magic, as they stated below:

"Three years ago, when they told me to go to a fortuneteller, my mother, a teacher, didn't believe me. I went out of necessity, and a fortuneteller prayed for my brother" (P 10).

Increasing knowledge: Families of people with schizophrenia should learn more and clear up any confusion so they can meet the care needs of the person with schizophrenia. Lack of awareness among caregivers can be the most significant cause of role confusion. It can result in family members being less prepared to provide care because it can cause them to be released from the role and increase the caregiving burden. As one of them indicated:

"For example, I told you she used to stop her medications, but now we follow up completely because I know they get tired "(P2).

Emerging emotional behaviors: Because schizophrenia typically affects people in their teens, it paralyzes and shocks loved ones by making them feel like a family member has lost their ability to function. Some families of people with schizophrenia live in a constant state of grief, which makes it hard to continue in the role. Grief may appear in these families as new emotional behaviors like "crying" or "running and avoiding" one's position. Crying is a way to release emotional tension and show how you feel on the outside. However, it is not a good way to solve problems or deal with change, and it could even be harmful. Some families in this study could no longer handle the patients' issues and instead left them to deal with their symptoms independently. However, in some of them, the pressure was so great that they could no longer bear to care for their patients and considered quitting their job as a caregiver [44].

"They didn't teach us anything, for example, until two years after his hospitalization, when everyone suddenly jumped from sleep; we were all afraid." They didn't sympathize with us that you are like this; your soul is also damaged" (P4).

Fluctuating adaptation in the care of the schizophrenic patient: Corbin and Strauss point out that consequences result from practical, interactive, or emotional responses to events. Here, the preparedness of the caregiver led to a category called "fluctuating adaptation in the care of schizophrenia patients," which is explained below:

When a family member is diagnosed with schizophrenia, those who care for them learns to cope with the situation by using coping strategies. These ways of dealing with problems can be adaptive or maladaptive, depending on how much control the caregiver feels they have over the situation. Since schizophrenia is chronic, its symptoms change, and its severity varies from person to person; most families experience both sides of the spectrum and fluctuate between them. This category comprises "Hopeful mastery of the situation" and "Weakened power."

Hopeful master the situation: Most patients' families are disappointed when their loved one's symptoms relapse and become suspicious about the therapies. Despite this, some caregivers within families have optimism for the future. By learning more about the disease as a whole, they may show positive adaptive responses and be able to control the disease's symptoms better. As a result, they are under less caregiving pressure and have more control over their current situations. As one of the caregivers said:

"With a lot of effort and hope, I sent a person who could not even take care of himself to society so that he could work and help me, his mother, even financially" (P12).

Weakened power: Most family caregivers experience a loss of power during their lifetime because of the caregiving burden. Some of the caregivers suffered from psychosomatic disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome, migraines, heart attacks, etc., caused by the psychiatric diseases of their families. Due to the genetic nature of psychiatric problems, these people may have mental disorders or be under too much pressure to care for others. They may feel anxiety, stress, and depression, sleep problems, fear, guilt, and self-blame. One of the psychiatrists recounts her experience like this:

We must explain to them, for example, the cause of their child's illness." "Many caregivers feel guilty that maybe they did not do enough for their child to become like this" (P14).

Core category and theory

In this section, we first explain the core category and then present the theory of "The process of caregiver preparedness in family caregivers of schizophrenia patients."

The core category: Adaptive endeavor

According to the participants' primary concern, "compassion fatigue," the interviews and data analysis showed that family caregivers address the main problem by utilizing strategies such as taking refuge in pseudo-scientific solutions, increasing knowledge, and showing emotional behaviors throughout the "adaptive endeavor." We talked about this concept in detail in previous sections.

Theoretical explanation of "fluctuating adaptation in caregivers of schizophrenia patients: The process of caregiver preparedness in their families."

All family caregivers of schizophrenia patients had difficulties coping with their role as caregivers. The main concern of this theory was "compassion fatigue" caused by contextual factors, including "encountering the crisis of the unknown," "confronting mental health inequalities in society," and "role confusion." Family caregivers of schizophrenia patients utilize some coping strategies toward the primary concern of "adaptive endeavor," which is the core category of this theory. Using these strategies had good and bad results, so the families had to change how they cared for their loved ones.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to explore how family caregivers of people with schizophrenia get ready to care for them. This theory is made up of six ideas: "encountering the crisis of the unknown," "confronting mental health inequalities in society," "role confusion," "facilitating family-centered care," "adaptive endeavor," and "fluctuating adaptation in the care of schizophrenia patients." Figure 1 provides a holistic view of the most prominent components of this theory.

Our research showed that a caregiver's knowledge is one of the most critical factors in caregiving preparedness. In contrast to this study, family caregivers' knowledge of stroke survivors was linked to their readiness to care for them [21]. Also, previous phenomenological research found that family caregivers of palliative care patients were not ready for the unknown [22]. In another study, family caregivers of cancer patients said that knowledge was the most crucial part of being ready [13]. In the current study, the family caregivers did not know enough about the nature of the disease, how to deal with it healthily, and what medications to give. They also needed more support resources. Studies done in Iran that asked family members of people with schizophrenia about their experiences confirm this.

Also, these studies showed that mental health inequalities are more visible in a developing country like Iran for the following reasons: Lack of community mental health services, negative attitude toward mental illnesses, shortage of insurance coverage, lack of education and support systems for rehabilitation of people with mental health problems, and finally, the collectivist culture, which results in more stigma [23-28]. In contrast to these studies, Darban, et al.'s qualitative research in 2021 showed that families find it hard to deal with the condition because there are insufficient social support services. Therefore, they will achieve strength and empowerment in caregiving [29].

On the other hand, Akbari, et al. said in their narrative review that most family caregivers will experience mourning symptoms if they do not get enough social, financial, spiritual, and psychological support. This is similar to what we found in our study about role confusion [24]. Erikson's theory of developmental stages discusses the idea of role confusion [30]. Even though this study found that it is harder for families of people with schizophrenia to be ready to care for them as they change roles, it is accompanied by the experience of mourning, which is labelled as a subjective and objective burden in Lippi's study and makes families give up their caring role or look for help from others [10]. Some studies showed a reverse correlation between caregivers' burden and their preparedness [15,31-36]. Another qualitative study showed that family caregivers in Iran also feel these subjective and objective burdens [37]. They called it "living in hell." In our study, family caregivers talked about how centered-family care could help ease these burdens and make caregiving easier. In addition to what we found in our study, Barbara et, al. also indicated that the assessment of family expectations and their needs is a vital part of getting families of stroke patients ready to be caregivers [38]. In this context, Akbari, et al. looked at the theme of "not meeting the needs of caregivers" as one of the significant problems for families [24]. Also, Pritchard, et al. showed that some of the caregivers' characteristics could predict caregiving readiness, as we identified them as "internal motivators" in families of schizophrenia patients [14].

Ultimately, all of these outside factors can lead to "compassion fatigue" in family caregivers of people with schizophrenia. Compassion fatigue is when caregivers feel physically and mentally worn out from taking care of long-term patients for a long time [39]. This theme is similar to one of the themes of qualitative studies done on the families of people with schizophrenia [40]. Previous studies also found that family caregivers of chronic patients experienced compassion fatigue [41-44].

Family caregivers in our study used adaptive endeavor coping strategies to combat compassion fatigue. In line with our findings, one of the Iranian studies pointed out that seeking information as a problem-focused and emerging emotional behavior is an emotionfocused strategy in family caregivers of schizophrenia patients [45]. Similar to what we found, other studies found that resignation, escape tendencies, and avoidance was more common ways for families of schizophrenia patients to deal with stress [46-49]. Also, in line with what we found, one study showed that fortune-telling and rituals are considered non-halal in Muslim culture and are used by some caregivers out of necessity [50]. Not only do Muslims talk about these traditional and pseudoscientific practices, but so do scholars from other countries. These practices include fortune telling, worshippingg ancestors, believing in Buddhist gods, and believing in gods from history who helped people. According to these studies, when the patient's family does not believe in psychiatric treatments or is disappointed with scientific treatments, they turn to these traditional ones, which were discussed in our study as one of the coping mechanisms [51-53].

In our theory, these coping strategies lead to fluctuating adaptation in schizophrenia patients' care. Because schizophrenia is a long-lasting and deliberating disease, families experience both good and bad things, such as hope and a loss of power. In their study, Ebrahim pour, et al. found that caring for people with schizophrenia led them "to grin and bear with the disease" [54]. This dualism is also evident in Stanley's results. Caregiving has a dual nature: On the one hand, it requires sacrifice out of love for one's family, which fosters empathy, affection, and unity within one's family. On the other hand, caring responsibilities can put much stress on the family, which can be harmful [55]. Even though an Iranian study focused on the positive achievements of families, who struggled with schizophrenia patients [29].

Based on what we found, this theory explains how families of people with schizophrenia get ready to care for them. This can help health professionals figure out how ready the caregiver is before the patient goes home. They can assess the family caregivers' needs, expectations, and unknowns. Also, they can help them choose effective ways to deal with the change in their role. Health policymakers can also put policies in place to remove the barriers to caregiving preparedness or develop a program for community health nursing [56].

Limitations and Strengths

This qualitative investigation has several limitations. During COVID-19, most interviews were done online or over the phone out of respect for the law and people's health and safety. Most nonverbal clues and body language may need to be taken into account, which could make it hard for the researcher to understand the interviews correctly. The second barrier was the gender of the caregivers. Most of this study's participants were female, which might impact transferability. In Iran, like in other cultures, women care for sick family members [56]. The last restriction concerned the age of family caregivers. Since most of the interviews were done online, older family caregivers could not participate in our research. Because elderly caregivers were at a greater risk for COVID-19, they did not visit hospitals. Even though the virtual interview is hard, this method is suitable for stigmatized groups like people with schizophrenia and their family caregivers. It could protect the interviewee's privacy and does not have to consider the interview's time, place, or cost. The second strength was the choice of family caregivers, which had the most variation between the different categories. A further action research study is recommended to put this theory into practice.

Conclusion

In summary, this is the first qualitative study to look at how family members of people with schizophrenia take care of them. The results showed what the families were most worried about and how they tried to deal with it. Knowing the process's challenges and benefits can help us guess how the caregivers will prepare. Because caregiver preparedness can change over time, schizophrenia patients and their families must be followed up after discharge.

Ethical Considerations

The ethics committee approved the present study of the Islamic Azad Tehran University of Medical Sciences with the code IR.IAU.TMU.REC.1400.143.

Authors' Contributions

The first author talked to the participants, and all authors interpreted the results and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interests

There is no conflict of interest in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Islamic Azad University of Tehran Medical Sciences for its financial support and the cooperation of family caregivers and healthcare providers participating in this study.

References

- McCutcheon, Robert A, Tiago Reis Marques, and Oliver D Howes. "Schizophrenia-an overview." JAMA Psychiatry 77 (2020): 201-210.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collaborators GBD. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. (2018).

- Fitryasari, Rizki, Ah Yusuf, Rr Dian Tristiana, and Hanik Endang Nihayati, et al. "Family members' perspective of family Resilience's risk factors in taking care of schizophrenia patients." Int J Nurs Sci 5 (2018): 255-261.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amedu MA, OI Obekpa, IA Audu, and CO Okaro, et al. "Relationship between Cost of Treatment of Schizophrenia and Caregiver Burden in Northern Nigeria." Benue J Med 1 (2022): 15-24.

- Patel, Vikram, and Somnath Chatterji. "Integrating mental health in care for noncommunicable diseases: An imperative for person-centered care." Health Aff (Millwood) 34 (2015): 1498-1505.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, Sami H, Ebtihaj O Fallata, Marwa A Alabdulwahab, and Wesam A Alsafi, et al. "Assessment of the burden on caregivers of patients with mental disorders in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia." BMC Psychiatry 17 (2017): 1-8.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Yunan, Victor Ngo, and Sun Young Park. "Caring for caregivers: Designing for integrality." In Proceedings of the 2013 conference on Computer supported cooperative work, pp. 91-102. (2013).

- Archbold PG. "The clinical assessment of mutuality and preparedness in family caregiver to frail older poaple." Key aspects of elder care (1992): 328-339.

- Mueser, Kim T, and Susan Gingerich. The complete family guide to schizophrenia: Helping your loved one get the most out of life. Guilford Press, (2006).

- Lippi, Gian. "Schizophrenia in a member of the family: Burden, expressed emotion and addressing the needs of the whole family." S Afr J Psychiatr 22 (2016): 1-7.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Panayiotopoulos, Christos, Andreas Pavlakis, and Menelaos Apostolou. "Family burden of schizophrenic patients and the welfare system; the case of Cyprus." Int J Ment Health Syst 7 (2013): 1-9.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khan, Saira, and Barira Munir. "Attitude of Caregivers of the Patient with Schizophrenia." Pak J Physiol 15 (2019): 57-59.

- Mazanec, Susan R. "Perceived needs, preparedness, and emotional distress of male caregivers of postsurgical women with gynecologic cancer." Number 2/March 2018 45 (2018): 197-205.

- Pritchard, Elizabeth, Amy Cussen, Veronica Delafosse, and Miriam Swift, et al. "Interventions supporting caregiver readiness when caring for patients with dementia following discharge home: a mixed-methods systematic review." Australas J Ageing 39 (2020): 239-250.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hoseinpoor, Moosa, Kian Nourozi, Abolfazl Rahgoi, and Sima Ghasemi, et al. "The Relationship between Care Burden, Care Preparedness and the Quality of Life in the Home Caregivers of the Elderly with the Alzheimer's Disease in Iran Alzheimer’s Association." J Gerontol 6 (2021): 10-18.

- Li, Yuruo, Natalie Slopen, Tracy Sweet, and Quynh Nguyen, et al. "Stigma in a collectivistic culture: Social network of female sex workers in China." AIDS Behav (2021): 1-13.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stone, Karon. "Enhancing preparedness and satisfaction of caregivers of patients discharged from an inpatient rehabilitation facility using an interactive website." Rehabil Nurs 39 (2014): 76-85.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hudson, Peter, and Sanchia Aranda. "The Melbourne Family Support Program: evidence-based strategies that prepare family caregivers for supporting palliative care patients." BMJ Support Palliat Care 4 (2014): 231-237.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory: Sage publications, (2014).

- Lincoln, Yvonna S, and Egon G Guba. "But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation." New directions for program evaluation 1986 (1986): 73-84.

- Liu, Juanjuan, Qi Liu, Yanjin Huang, and Wen Wang, et al. "Effects of personal characteristics, disease uncertainty and knowledge on family caregivers' preparedness of stroke survivors: a cross-sectional study." Nurs Health Sci 22 (2020): 892-902.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mason, Naomi, and Suzanne Hodgkin. "Preparedness for caregiving: A phenomenological study of the experiences of rural Australian family palliative carers." Health Soc Care Community 27 (2019): 926-935.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimpour Mouziraji, Zeinab, Akram Sanagoo, and Leila Jouybari. "Lived Experiences of a Family with a Patient with Schizophrenia." Iran J Psychiatry 9 (2021): 99-109.

- Akbari, Mohammad, Mousa Alavi, Alireza Irajpour, and Jahangir Maghsoudi, et al. "Challenges of family caregivers of patients with mental disorders in Iran: A narrative review." Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res 23 (2018): 329.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tamizi, Zahra, Masoud Fallahi-Khoshknab, Asghar Dalvandi, and Farahnaz Mohammadi-Shahboulaghi, et al. "Caregiving burden in family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia: A qualitative study." J Educ Health Promot 9 (2020): 12.

- Mohamad, MS, P Zabidah, I Fauziah, and N Sarnon, et al. "Mental health literacy among family caregivers of schizophrenia patients." Asian Soc Sci 8 (2012): 74.

- Shamsaei, Farshid, Fatemeh Cheraghi, and Ravanbakhsh Esmaeilli. "The family challenge of caring for the chronically mentally ill: A phenomenological study." Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci 9 (2015).

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Manesh, Azadeh Eghbal, Asghar Dalvandi, and Mohammad Zoladl. "The experience of stigma in family caregivers of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A meta-synthesis study." Heliyon 9 (2023).

- Darban, Fatemeh, Roghayeh Mehdipour-Rabori, Jamileh Farokhzadian, and Esmat Nouhi, et al. "Family achievements in struggling with schizophrenia: Life experiences in a qualitative content analysis study in Iran." BMC Psychiatry 21 (2021): 1-11.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kidwell, Jeannie S, Richard M Dunham, Roderick A Bacho, and Ellen Pastorino, et al. "Adolescent identity exploration: A test of Erikson's theory of transitional crisis." Adolescence 30 (1995): 785-794.

[Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karabulutlu, Elanur Yılmaz, Gulcan Bahcecioglu Turan, and Safiye Yanmıs. "Evaluation of care burden and preparedness of caregivers who provide care to palliative care patients." Palliat Support Care 20 (2022): 30-37.

- Scherbring, Mary. "Effect of caregiver perception of preparedness on burden in an oncology population." In Oncology nursing forum 29 (2002).

- Scherbring, Mary. "Effect of caregiver perception of preparedness on burden in an oncology population." Oncol Nurs Forum 29 (2002).

- Lieshout, Kirsten, Joanne Oates, Anne Baker, and Carolyn A Unsworth, et al. "Burden and preparedness amongst informal caregivers of adults with moderate to severe traumatic brain injury." Int J Environ Health Res Public Health 17 (2020): 6386.

- Turan, Gulcan Bahcecioglu, Nuray Dayapoglu, and Zulfünaz ozer. "Evaluation of care burden and caregiving preparedness in caregivers of patients with epilepsy: A sample in eastern Turkey." Epilepsy Behav 124 (2021): 108370.

- Nguyen, Huong Q, Eric C Haupt, Lewei Duan, and Anthony C Hou, et al. "Hospital utilisation in home palliative care: caregiver health, preparedness and burden associations." BMJ Support Palliat Care (2022).

- Molavi, Parviz, Saeid Sadeghieh-Ahary, Mohsen Rezaeian, and Elmira Taghizadeh, et al. "Living in Hell": Experiences of Iranian Families Living with Patients with Schizophrenia. (2021).

- Lutz, Barbara J, Mary Ellen Young, Kerry Rae Creasy, and Crystal Martz, et al. "Improving stroke caregiver readiness for transition from inpatient rehabilitation to home." Gerontologist 57 (2017): 880-889.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Beth Perry, RN, and RN Margaret Edwards. "A Qualitative Study of Compassion Fatigue among Famly Caregivers in Long-Term Care Homes." Perspect 38 (2015): 14.

- Upasen, Ratchaneekorn, and Weeraphol Saengpanya. "Compassion fatigue among family caregivers of schizophrenic patients." J Popul Soc Stud 30 (2022): 1-17.

- Day, Jennifer R, Ruth A Anderson, and Linda L Davis. "Compassion fatigue in adult daughter caregivers of a parent with dementia." Issues Ment Health Nurs 35 (2014): 796-804.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murkute, Ujjwala, and Ujjawala Veer. "A Descriptive Study to Assess Compassion Fatigue and Compassion Satisfaction among Caregivers of Patients undergoing Chemotherapy in selected Hospital in a City of India." Inter J Nurs Midwi Res 8 (2021): 2-8.

- Davenport, Stacy, and Tara Rava Zolnikov. "Understanding mental health outcomes related to compassion fatigue in parents of children diagnosed with intellectual disability." J Intellect Disabil 26 (2022): 624-636.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Allday, R Allan, Jason M Newell, and Yevheniy Sukovskyy. "Burnout, compassion fatigue and professional resilience in caregivers of children with disabilities in Ukraine." Eur J Soc Work 23 (2020): 4-17.

- Rahmani, Farnaz, Fatemeh Ranjbar, Mina Hosseinzadeh, and Seyed Sajjad Razavi, et al. "Coping strategies of family caregivers of patients with schizophrenia in Iran: A cross-sectional survey." Int J Nurs Sci 6 (2019): 148-153.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shoib, Sheikh, Soumitra Das, Anoop Krishna Gupta, Tamkeen Saleem, and Sheikh Mohd Saleem. "Perceived stress, quality of life, and coping skills among patients with schizophrenia in symptomatic remission." Middle East Curr Psychiatry 28 (2021): 1-8.

- Haman, Generosus Magnum Marianus, Tadeus AL Regaletha, and Dominirsep O Dodo. "Coping Strategies in Patients with Schizophrenia at Naimata Mental Hospital." Timorese J Public Health 2 (2020): 97-109.

- Rollins, Angela L, Gary R Bond, Paul H Lysaker, and John H McGrew, et al. "Coping with positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia." Am J Psychiatr Rehabil 13 (2010): 208-223.

- Holubova, Michaela, Jan Prasko, Radovan Hruby, and Dana Kamaradova, et al. "Coping strategies and quality of life in schizophrenia: cross-sectional study." Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 11 (2015): 3041-3048.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vanaleesin S, W Suttharangsee, and U Hatthakit. "Cultural aspects of care for Muslim schizophrenic patients: an ethnonursing study." Songklanagarind M J 25 (2020): 361-370.

- Huang, Charles Lung-Cheng, Chi-Yung Shang, Ming-Shien Shieh, and Hsin-Nan Lin, et al. "The interactions between religion, religiosity, religious delusion/hallucination, and treatment-seeking behavior among schizophrenic patients in Taiwan." Psychiatry Res 187 (2011): 347-353.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, Margaret Cheng, Kathy Niu, Fuzhong Yang, and Guohua Xia, et al. "Culturally Confounded Diagnostic Dilemmas: When Religion and Psychosis Intersect." Harv Rev Psychiatry 27 (2019): 201-208.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yip, Kam-shing. "Traditional Chinese religious beliefs and superstitions in delusions and hallucinations of Chinese schizophrenic patients." Int J Soc Psychiatry 49 (2003): 97-111.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stanley, Selwyn, and Sujeetha Balakrishnan. "Informal caregiving in schizophrenia: correlates and predictors of perceived rewards." Soc Work Ment Health 19 (2021): 230-247.

- Sharma, Nidhi, Subho Chakrabarti, and Sandeep Grover. "Gender differences in caregiving among family-caregivers of people with mental illnesses." World J Psychiatry 6 (2016): 7.

[Crossref] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J Kessa, Alexandra E Pavlakis, and Meredith P Richards. "It’s more complicated than it seems: Virtual qualitative research in the COVID-19 era." Int J Qual Methods 20 (2021).

Citation: Manesh, Azadeh Eghbal, Mohammad Zoladl and Asghar Dalvandi. "Fluctuating Adaptation in Caregivers of Schizophrenia Patients: The Process of Caregiver Preparedness in Their Families-A Grounded Theory Study." Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses 17 (2023).

Copyright: © 2023 Manesh AE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the creative commons attribution license which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.